Happy Wednesday, Fireshed community!

Last month we covered the difference between two parts of the fire management triangle - ignitions prevention and fuels reduction. Today we will be discussing the last piece of that triangle - fire suppression - and how it differs from fire exclusion. The West has a long and complicated history with both suppression and exclusion, and this history influences how hot, fast, and frequently wildfires burn in the current day.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features:

A brief history of wildfire in the West

Differences between fire exclusion and fire suppression

Upcoming webinars and workshops

Take care as spring rolls in,

Rachel

Wildfire in the West

European colonization

Homo sapiens, and before them Homo erectus, have been using fire for more than 400,000 years. Indigenous peoples across the continent have been using fire since at least 12,550 BCE for a range of objectives such as hunting, crop management, increased plant yield, pest management, fire hazard reduction, and warfare, as well as managing fuels around communities. Early Americans selectively controlled fires burning close to or threatening their communities but left others to burn uninhibited. As explained by the Karuk Tribe Climate Change Projects, “unlike widespread conceptions of fire as ‘bad,’ fire is an essential component of [our] cultural practice and ecosystem health. Fire is medicine. Fire is referenced in our creation stories and is part of our world renewal ceremonies.”

Western expansion brought an uptick in fire activity due to land clearance, logging, agriculture, and railroads during Euro-American settlement, reaching a peak in the mid-1800s. Close to the end of that century, widespread domestic livestock grazing reduced grassy fuel loads, compacted soils, and greatly reduced fire frequencies. Landscape fragmentation from trail and road building and a sometimes-violent prohibition of indigenous burning practices further limited the spread of fire. By the 1890s, Euro-American settlement-colonization resulted in an emphasis on suppression of wildfires. (Long-term perspective on wildfires in the western USA)

The Big Burn

1905 marked the creation of the U.S. Forest Service, whose primary purpose was to "to sustain healthy, diverse, and productive forests and grasslands for present and future generations". Wildfire was seen as a threat to those productive forests. This mode of thinking was solidified five years later with "The Big Burn" in 1910, the largest wildfire in U.S. history which burned 3 million acres in two days and killed 87 people in eastern Washington, Idaho and Montana. The Big Burn prompted the conservation of America's forests and the creation of public lands but also ensured that over the next 90 years, suppression became the default land management approach to wildfire. This strategy was cemented into federal policy in multiple instances, the most notable of which was the US Forest Service’s 1935 implementation of the so-called “10:00 AM Policy”, dictating that all wildfire ignitions should be contained and extinguished by 10 o’clock the morning after they began.

As years passed and fires were both excluded from the landscape and actively suppressed, organic fuels accumulated on the forest floors, trees encroached into areas which were previously maintained as meadows by naturally occurring fire, and the West became increasingly more flammable.

Recognition of fire as a natural process

In 1968, the Park Service began to allow lightning-started "prescribed natural fire" to burn within predefined management units in the wilderness, a model which is still in play today. By the late 1980s, the departments of agriculture and the interior were reconsidering the fundamental importance of fire's natural ecological role, but it wasn't until 1995 that the Forest Service introduced legislation allowing lightning-caused fires to burn in wilderness. In 2000, the National Fire Plan was introduced to strike a balance between actively responding to severe wildland fires and their impacts to communities and ensuring landscape restoration through sufficient hazardous fuels reduction and firefighting capacity for the future. Fourteen years later, the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior worked with a collaborative interdisciplinary team to establish the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy "to safely and effectively extinguish fire when needed; use fire where allowable; manage natural resources; and as a nation, to live with wildland fire.” This 2014 document informs current central fire preparedness and response through three tenants:

Restore and maintain resilient landscapes

Create Fire Adapted Communities (FAC)

Safe and effective wildfire response

“In recent decades the U.S. government has officially accepted the idea of restoring fire to public lands wherever doing so will not endanger firefighters or nearby residents. That means using planned burns to clear overgrown lands and letting some wildfires in remote areas burn under supervision instead of putting them out.” Land managers face an increasingly complex set of circumstances as they try to reintroduce fire in a controlled manner to the fire-starved West: “residential development has spread into fire-prone areas, creating pressure to protect exurban homes, and climate change has made some areas, especially the West, hotter, drier and more fire-prone.” (Jennifer Weeks, The Fire Historian)

Fire Exclusion vs Fire Suppression

Fire suppression

Fire suppression refers to a range of operations used to extinguish a wildfire or prevent or modify the movement of unwanted fire. Firefighters control a fire's spread (or put it out) by removing one of the three ingredients fire needs to burn: heat, oxygen, or fuel. They remove heat by applying water or fire retardant on the ground or by air. They remove fuel by cutting and digging to remove burnable vegetation with hand tools, by using heavy equipment like bulldozers to clear large areas of brush and trees, and by deliberately setting fires to rob an approaching wildfire of fuel (fighting fire with fire). (US DOI)

Fire suppression is needed to protect homes, businesses, recreation and cultural sites, and other values that could be at risk of loss when a wildfire burns through. Suppression puts an emphasis, first and foremost, on firefighter safety, while taking into consideration a plethora of other factors - location, timing, fuel type, resources available, and more. While the technology to assist with wildfire suppression decisions (such as PODS) is advancing, so is the cost; the total cost of wildfire suppression in 2021 was over $2.8 billion.

A coordinated effort to minimize the threat of wildfires made fire suppression the default response by federal, state, and local entities for decades, resulting in the near eradication of wildfires from the landscape. However, successful wildfire suppression has resulted in accumulated fuels that lead to larger and more severe wildfires in the long-term—what is known today as the “wildfire paradox.”

Fire exclusion

According to the US Forest Service, Fire exclusion is “the effort of deliberately excluding or preventing fire in an area regardless of [whether] the fire is natural or human caused.” Fire can be excluded through a number of intentional actions such as wildland fire control lines and environmental planning which designates some areas as protected activity centers. It can also be excluded unintentionally through activities such as landscape fragmentation and heavy grazing which removes all of the fine fuels, such as grasses and shrubs, necessary to carry low-intensity fire across the landscape.

“There have been marked human influences on western wildfires since Euro-American settlement, including increased ignitions (e.g., from forest clearance, agriculture, logging, and railroads), and fire exclusion. Other significant impacts on vegetation and fire occurred indirectly, such as changes in plant succession pathways and the introduction of nonnative species.” (Long-term perspectives on wildfires) As ecosystems have evolved with fire, so too have the plants and animals. Human activities have altered many of the relationships between fire and plants and animals.

“The impact of fire exclusion on vegetation structure and composition [combined with drought, pests, and disease] leads to fuels that, when ignited, burn hotter, spread faster, last longer, and cover more area than they did under more natural conditions.” (NIFC, Communicator's Guide for Wildland Fire Management) The exclusion of fire from the landscape also creates a situation of denied access for indigenous and traditional communities to spiritual practices and traditional foods, puts cultural identity at risk, and infringes upon political sovereignty.

The takeaway

“There is growing recognition that past land use practices, combined with the effects of fire exclusion, has resulted in heavy accumulations of dead vegetation, altered fuel arrangement, and changes in vegetative structure and composition. When dead fallen material (including tree boles, tree and shrub branches, leaves, and decaying organic matter) accumulates on the ground, it increases fuel quantity and creates a continuous arrangement of fuel. When this occurs, surface fires may ignite more quickly, burn with greater intensity, and spread more rapidly and extensively than in the past.” (NIFC)

While wildfires must be suppressed sometimes in some locations, land managers are recognizing that we cannot continue to suppress our way out of increasingly severe and lengthy fire seasons. Mindful reintroduction of ecologically appropriate fire to fire-adapted landscapes, creation of resilient and fire-ready communities, and other climate resiliency work are all part of the solution.

Upcoming Opportunities

Webinars

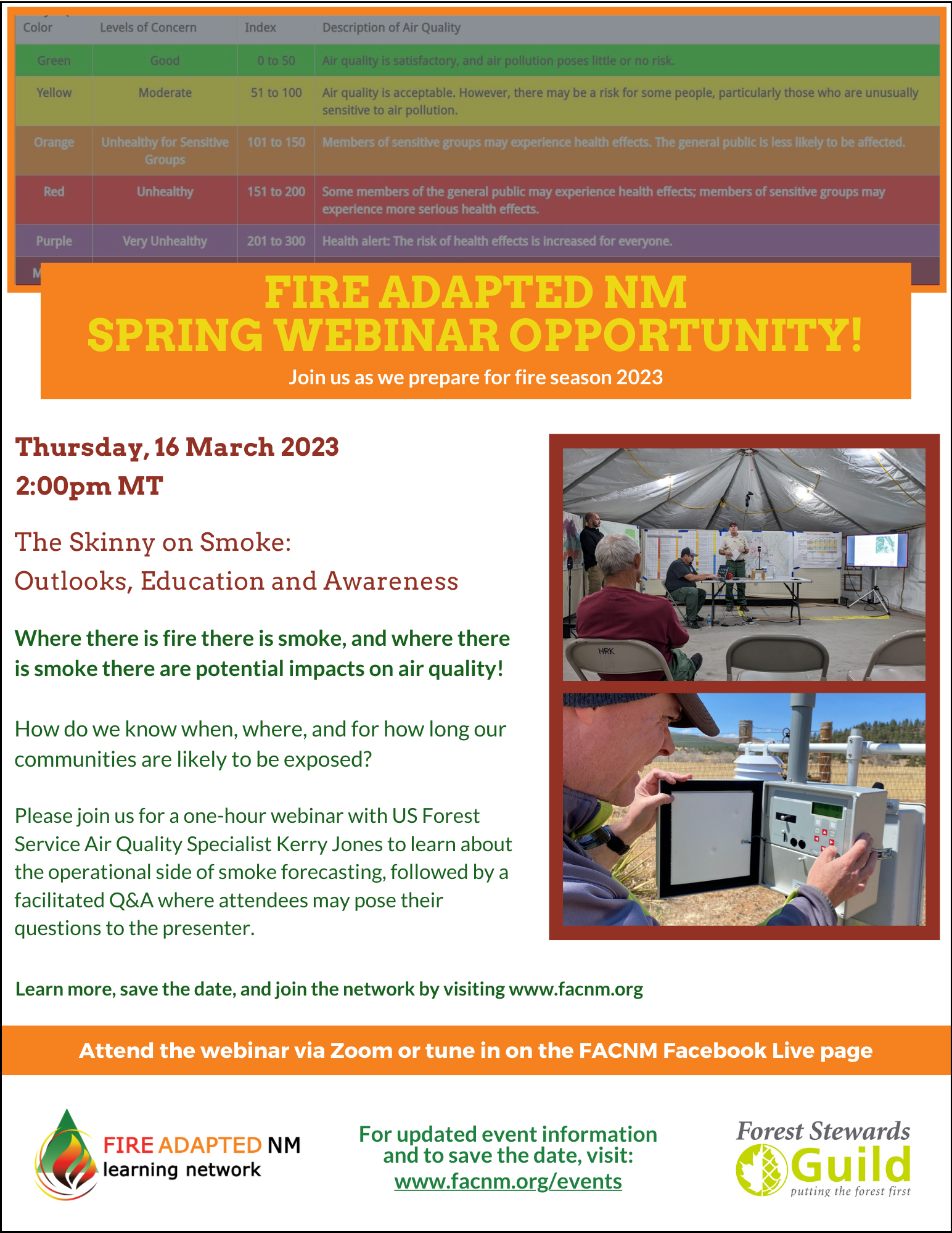

The Skinny on Smoke - Outlooks, Education and Awareness

Join us as Air Quality Specialist Kerry Jones discusses various facets of smoke projections, including what goes into generating seasonal outlooks and fire weather forecasts, the weather conditions that are most conducive to fire and to smoke, and how determinations of air quality are made along with the decision to send air quality advisory alerts out to the public.

When: Thursday, March 16, 2023, 2:00pm - 3:00pm

Where: Virtual Zoom event - register now

Strategies to reduce wildfire smoke in frequently impacted communities

The SW and NW Fire Science Consortiums and Forest Stewards Guild present a one-hour webinar with USFS speaker Rick Graw on proactive and adaptive land management strategies to reduce wildfire smoke in frequently impacted communities. This webinar focuses on research from the Pacific Northwest but is applicable to land managers and fire adapted communities practitioners everywhere.

When: Tuesday, March 21, 2023, 12:00pm - 1:00pm

Where: Virtual Zoom event - register now

Workshops

Ready, Set, Go! Wildfire Preparedness Workshop

Join us to take positive steps toward building a Fire Adapted Community! This workshop will feature information about wildfire risk in the Santa Fe Fireshed, a presentation by representatives from the Wildfire Research Center, a mini-training on how to conduct a home hazard assessment, what to include in a Ready, Set, Go kit, and much more. Get information and help from experts from the Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition, Forest Stewards Guild, City of Santa Fe Fire Department, and Villages of Santa Fe. This workshop is free and open to the public.

When: Saturday, March 18, 2023, 10:00am - 12:30pm

Where: Christ Church Santa Fe PCA, 1213 Don Gaspar Ave, Santa Fe, NM 87505