Happy Wednesday, Fireshed Community!

Over the past decade, the wildland fire community has been experiencing a paradigm shift from thinking of wildfire resilience in simple terms to recognizing the complexities of risk. An emerging theme within this shift is that simple conceptualizations of risk do not account for the social and ecological diversity of fire-prone areas. From international organizations to grassroots efforts, those groups working to address our wildfire dilemma and work for better fire outcomes are working together to better account for diversity of perspectives and experiences in wildfire preparedness.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features:

Recommendations and considerations on diversity in fire adaptation

Vulnerability to Wildfire: Going Beyond Wildfire Hazard Analysis

Better Fire Adaptation: Increasing Efficacy Through Comprehensive Risk Analysis and Collaboration

Living with Fire: the Influence of Local Social Context and Need for Diversity

Be well,

Rachel

Wildland Urban Fire Summit

The 2024 New Mexico Wildland Urban Fire Summit (WUFS) is happening October 8-10 at the Sagebrush Inn in Taos, NM! This is a space for community members, fire service volunteers and professionals, non-profit conservation groups, and federal, state, and local government representatives to gather and discuss challenges, innovations, and solutions for engagement in fire adaptation. During the in-person event, local community members will share regional history and discuss living in and adapting to the Wildland Urban Interface.

This year, the summit will focus on strengthening partnership through diverse perspectives – taking action in the WUI, including how new partners are developed, revitalizing or strengthening existing partnerships, and how the perspectives and resources they can provide help us to take action in our communities.

Agenda highlights include:

Welcome from NM State Forester Laura McCarthy

Property insurance & home mitigation

Taos-region focus & field trip (Wednesday)

Emergency communications

Finding and using funding

Ruidoso 2024 events

Diversity in Fire Adaptation: a Review

Researchers and practitioners from across the management spectrum have begun considering and making recommendations for how to make fire adaptation more diverse and reflective of physical communities, and therefore more effective and innovative, in recent years. Below is a brief collection of challenges, considerations, and recommendations for improving inclusion.

……….……….

Vulnerability to Wildfire: Going Beyond Wildfire Hazard Analysis

Massive wildfires, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change and a long history of fire-suppression, have strikingly unequal effects on minority communities. The Nature Conservancy recently highlighted a study which integrates the physical risk of wildfire with the social and economic resilience of communities to see which areas across the country are most vulnerable, a complexity acknowledged in their resulting “vulnerability index”. The results highlight the difference between wildfire hazard potential and wildfire vulnerability, showing that racial and ethnic minorities face greater vulnerability to wildfires compared with primarily white communities; in particular, Native Americans are six times more likely than other groups to live in areas most prone to wildfires. These findings “help dispel some myths surrounding wildfires — in particular, that avoiding disaster is simply a matter of eliminating fuels and reducing fire hazards or that wildfire risk is constrained to rural, white communities.”

The takeaway is that “ultimately it’s about connections, building relationships and breaking down cultural barriers that will bring us to a better outcome.”

Read the overview and dive into the study here.

……….……….

Incorporating Social Diversity into Wildfire Management

While research suggests that adoption or development of various wildfire management strategies differs across communities, there have been few attempts to design diverse strategies for local populations to better “live with fire.” Building on an existing approach, managers can adapt to social diversity and needs by using characteristic patterns of local social context to generate a range of fire adaptation “pathways” to be applied variably across communities. Each ‘pathway’ would specify a distinct combination of actions, potential policies, and incentives that best reflect the social dynamics, ecological stressors, and accepted institutional functions that people in diverse communities are likely to enact. This inclusion can help develop flexible scenario-based approaches for addressing wildfire adaptation in different situations.

Examples of unique pathway components for advancing fire adaptation through adaptive or collective action include:

Ways to promote property-level residential adaptation

Governance model/structure of collaborative processes

Fuels mitigation focus

Adaptation leadership and relationships

Incident Command teams and outside response

Wildfire impacts/short- or longer-term recovery

Mitigation aid or grants

Resource management focus

Means of communication, message framing

Read more about the pathways approach.

……….……….

More Effective Fire Adaptation Through Comprehensive Risk Analysis and Collaboration

Defining risk

The primary goal of simple risk approaches is to minimize the costs associated with hazards and their management. Simple risk approaches have their roots in actuarial insurance, risk management, and rational choice models.

The primary goal of complex risk approaches is not to minimize or eliminate immediate risk (as in simple risk approaches), but to adapt to the risk over time. Concepts of complex risk stem from scholarship on wicked problems, risk governance, and Second Modernity Risk. The complex risk framework accounts for and expands on simple risk ideas and approaches by explicitly considering the multiplicity of contexts, knowledges, and definitions regarding a particular hazard.

Moving from simple to complex and from exclusionary to inclusive

There is a prevailing tendency of wildfire management agencies and institutions to rely primarily on simple risk approaches to wildfire hazard management that focus on technical risk assessments, such as questions of probability of wildfire event occurrence, but do not reflect the complexity of contemporary wildfire risk. These insufficiently complex conceptualizations of risk do not incorporate and account for the social and ecological diversity of fire-prone areas, reducing options and creativity for addressing risk by disregarding the varied experiences and concerns that influence collective adaptation.

Approaching wildfire as a complex risk can increase adaptation to and coexistence with wildfire by recognizing and accounting for the complexities of wildfire governance amongst a variety of stakeholders who may operate at various scales using different knowledge systems. Such efforts are more likely to yield socially relevant and legitimate strategies for building wildfire adapted communities.

Although centralized simple risk approaches are an often-necessary part of addressing wildfire risk, greater emphasis on wildfire as a complex risk brings attention to the reality that wildfire response and consequences are interconnected - that is, that decisions and outcomes at various temporal points, including mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery, are linked to place-based networks, processes, activities, decisions, and outcomes of other temporal points.

Five principles to increase adaptation to and coexistence with fire through complex risk consideration

Embrace knowledge plurality and purposefully integrate perspectives other than technical expertise.

Including other types of expertise (and thus complexity), especially local definitions of risk and key values of concern, can increase the local relevance and legitimacy of the risk analysis which can be critical to local uptake and implementation.

Use inclusive, accountable, and transparent engagement strategies that incorporate collaborative learning processes.

Effectively implementing the first principle requires participation by a suite of interrelated public and private individuals in an iterative process to find pathways to desirable and feasible situational improvements.

Include underrepresented groups in collaborative processes and wildfire risk governing networks.

By forgoing assumptions that experts fully understand the experiences or abilities of underserved populations ( e.g., Latine, Black, Indigenous and People of Color), more inclusive processes invite more diverse perspectives and, by so doing, can better reflect the differential adaptation abilities of populations and organizations.

Account for potential uneven distributions of risk and resources to address risk.

Existing funding models for natural resource and associated wildfire management efforts tend to favor organizations with resources and capacity to pursue grants or whose views on wildfire risk match predominant policy priorities. As a result, groups or communities who have less access to resources and capacity may find their opportunities unchanged or even diminished, furthering an already uneven distribution.

Re-focus or re-balance investments across spatial, institutional, and temporal scales.

Wildfire investments which are currently concentrated on hazardous fuels reduction, preparedness (hiring and training firefighters), and response (incident management) could be re-focused to provide more resources to a wider range of pre-fire mitigation work and rapid post-fire adaptive recovery for those affected by fire. This means investing in systems of wildfire governance, the social architecture that will support collective action and innovation in ways that are more likely to be responsive to the changing circumstances of on-the-ground fire risk.

Learn more about recognizing complexity, and its inherent diversity, in fire management.

……….……….

Living with Fire: the Influence of Local Social Context and Need for Diversity

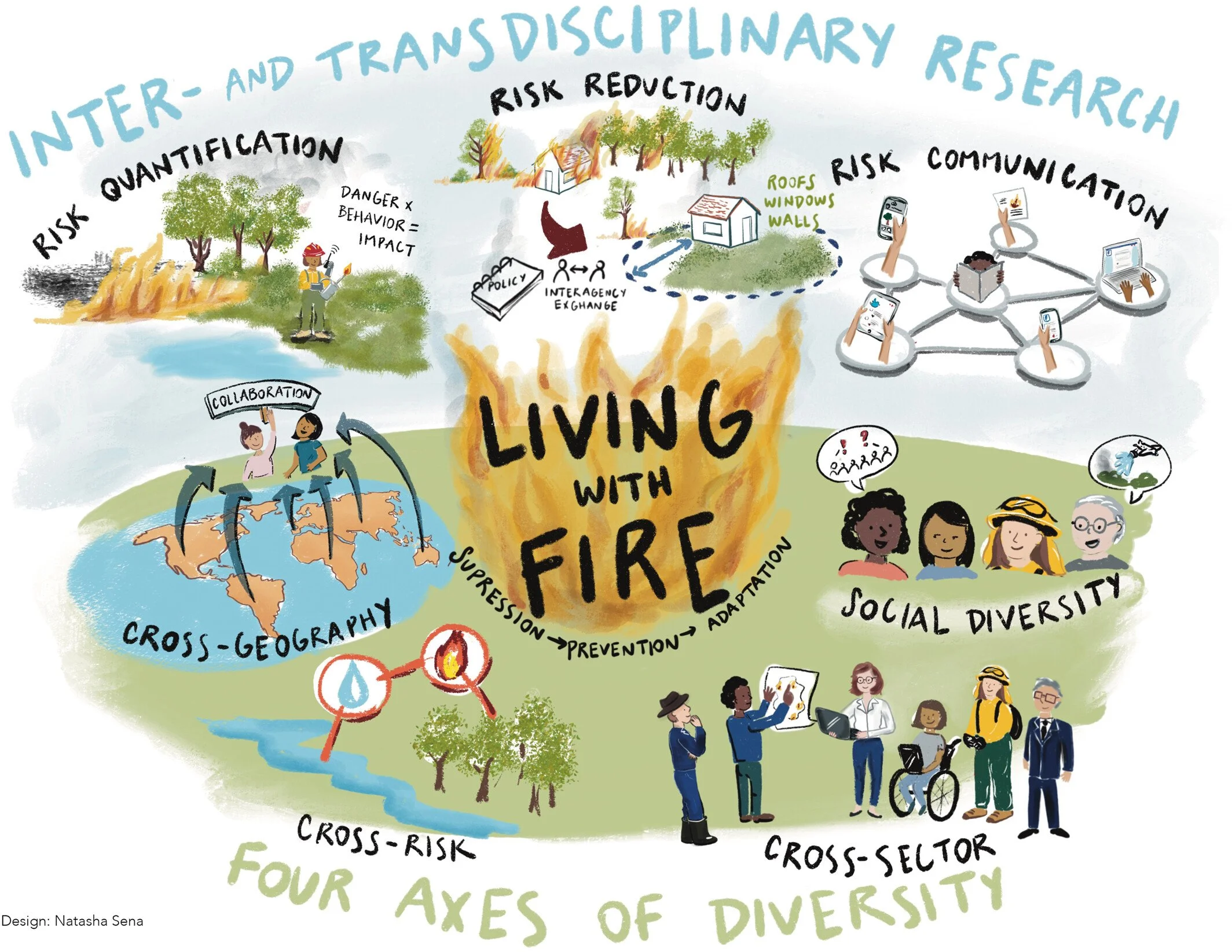

One element of meeting our contemporary wildfire challenge must be accepting fire in the landscape and working with instead of against it; essentially, to change our management paradigm from fire resistance to landscape resilience under the umbrella of Living with Fire. Achieving this integrated fire management approach will require a) understanding the intersecting drivers of fire impacts and risks and b) designing creative and effective risk reduction/management and communication strategies. The integrated fire management model that we are collectively moving toward must include innovation through exchange, adoption, and adaptation.

Living with fire rests on four essential pillars of diversity:

cross-geography (information and knowledge exchange between communities and countries);

cross-risk (learning from water and flood management);

cross-sector (connecting science and practice); and

social diversity (diversity of voices).

With regard to social diversity, there is a growing recognition that human adaptation to wildfire risk is a contingent exercise that may vary across diverse communities. A long history of social science indicates that any effort to improve adaptation is more likely to succeed when it adopts a holistic view of wildfire management that is tailored to emergent patterns of local social context. The unique combination of local history, culture, interpersonal relationships, trust in or collaboration with government entities, and place-based attachments that human populations develop in a given landscape all can have a large bearing on variable efforts to create fire adapted communities. These fundamental differences between and unique characteristics of individual communities can make a big impact on how planning documents (e.g. Community Wildfire Protection Plans), policies (e.g. homeowner risk mitigation requirements), mitigation implementation activities (e.g. home hardening), and education or assistance approaches are written or designed and how, or if, they are adopted by the local community in a meaningful way. Who is at the table and how space is created for everyone to engage matters.

Overall, fire researchers, practitioners, managers, and affiliates must better understand and design diverse strategies for fire adaptation that reflect the social diversity of human communities at risk from wildfire.

In the News

An article in the Santa Fe New Mexican, “Preparation for Wildfires in Santa Fe Starts at Home” recently highlighted the fire department’s community wildfire preparation services - and its wildland-urban interface specialist, Porfirio Chavarria (pnchavarria@santafenm.gov). It focuses on how individual actions tie into landscape-level preparation, saying “fires affect communities, not just individual properties,” and showcases some of the work that Santa Fe has done to improve wildfire outcomes for residents, including community education, wildfire mitigation agreements, home hazard analyses, the fire and weather alert system Alert Santa Fe, and future improvements such as rapid wildfire start detection.

Read more about these services and their success in the article.