Happy Wednesday and happy autumn, Fireshed Coalition!

As summer comes to a close, western skies continue to be filled with wildfire smoke from blazes in California, Oregon, Idaho, Washington, and other hot and dry forested states. Wildfires continue to follow the trend of igniting earlier and burning later into the year, breaking out of what we have traditionally thought of as ‘wildfire season’ and blurring the lines of property ownership and fire response decision jurisdiction as they race across entire landscapes. What can we do in response to ensure that our homes, businesses, and communities are ready for wildfire year-round?

Emerging guidance from the Institute for Home and Business Safety, United Policyholders, and others suggests that the best protection is strength in numbers. While single parcel defensible space and home hardening has been shown to work, it works a lot better when neighbors meet and do the work together, creating fuel breaks that protect the entire community, designing their defensible space together, and investing in neighborhood-wide protection plans, home hardening upgrades, safety ordinances, and more.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features:

Updated guidelines for individual parcel and community level fire preparedness

History and drivers of wildfire

The importance of community-level preparedness

Wildfire preparedness in action: residents and communities returning home after the fire

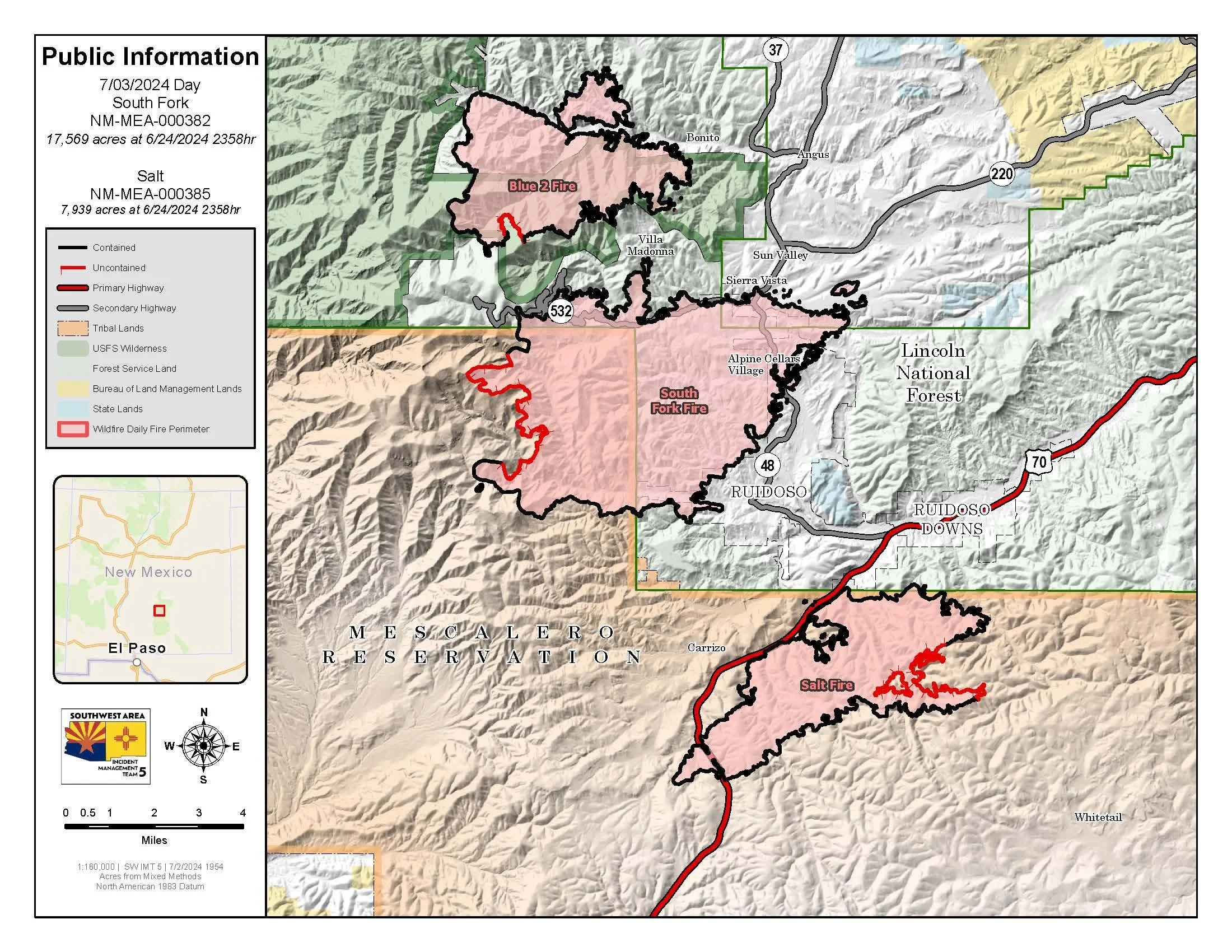

Salt Fork Fire, Village of Ruidoso, NM

Atlas Fire, Circle Oaks, CA

The importance of neighborhood ambassadors

Upcoming events

In the news

Be well and enjoy the equinox,

Rachel

Updated Fire Preparedness Guidelines

Expanding beyond individual parcels to encompass community readiness

The history and drivers of wildfire

For much of the West, fire is part of the natural landscape. However, wildfires become catastrophes when they burn at historically high severity, frequency, are driven by extreme weather, and move into our built environment. This can lead to uncontrollable structure-to-structure fire spread where an urban conflagration unfolds. Urban fire follows humans (population), drought, and wind. New Mexico has these all of these conflagration conditions:

The state has experienced the same population boom as the rest of the West, especially since 2020.

Almost all of New Mexico is in some state of drought and has been since 2019.

The state regularly experiences high wind, which often coincides with and exacerbates dry periods.

Urban firestorms have been a part of cities and their evolution across the globe for centuries. They have been applied as weapons of war as well. The 1666 London Fire was one of the first well documented urban conflagrations. It had similar characteristics to what we see in today’s wildfire-driven built environment conflagrations: drought conditions, human causation for ignition, and a high structure density with fuels between buildings. From the 1600s through the early 1900s, urban fire plagued cities globally (IBHS, The Return of Conflagration in Our Built Environment). Over the last century, we have solved this problem in our city centers but have recreated the risky conditions in our suburban and WUI areas.

The importance of community-level preparedness

The Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS) and other prominent fire preparedness organizations recommend using WUI code requirements to increase resilience, in addition to encouraging cities to make different individual, community, and policy choices. In this way, fire science can inform resilient thinking.

Critical elements of fire resilience:

Individual

A non-combustible “zone 0”.

Impenetrable vents and roofs.

Combustible elements between properties - find ways to break those connections.

Community

Parcel-level measures must be implemented at scale (such as fuel buffers along roads) so that communities can break the chain of conflagration and act as fuel breaks, not fuel sources.

Policy

Clustered financial incentives from the State to implement resilient retrofits (treat an entire neighborhood at once).

Require defensible space and fire-resistant design of new homes.

Most buildings are not designed to resist intense flame contact, and once ignited, they contribute as additional fuel to the fire. Therefore, to stall this “domino effect,” maintaining a proper separation between buildings is crucial in a resilient community. High fuel continuity, where fuels are densely distributed and interconnected, can promote the rapid spread of fire, as flames can easily move from one fuel source to another. The concept of fuel connectivity observed in vegetation fuels, such as grass and pine needles, can also be extended to structural fuels such as fences, sheds, accessory dwelling units (ADUs), and other similar objects. The underlying mechanism driving fire spread remains the same: when these structural fuels are closely spaced or connected, heat transfer between burned and unburned occurs at a high rate, leading to rapid fire spread.

It is important to thin, create defensible space, and implement home hardening measuring in and around your own home. It is equally important to talk to your neighbors about their fire risk, and hazards that you share, such as a coyote fence which separates your property but which would act as a connective wick for both homes during a wildfire. It takes action at all levels to prevent a fire becoming a conflagration.

Learn about these and other recommended actions as part of the new Wildfire Prepared Home program from IBHS, a designation program which enables homeowners to take preventative measures for their home and yard to protect against wildfire.

Wildfire Preparedness in Action: success stories from the frontlines

Home hardening, defensible space, and fire ordinances: lessons from the South Fork Fire, NM, 2024

Dick Cooke, Forester for the Village of Ruidoso and FACNM Leader, has been working for a long time to prepare the village for a wildfire. Those preparations were tested when, in June 2024, the South Fork Fire exploded to 15,000 acres in its first 24 hours and rapidly approached the community with ember showers falling a mile in front of the crowning flaming front.

As Dick recounts, when the fire hit the village boundary, it almost immediately dropped from the tree crowns to the ground, creating a more favorable environment for firefighters to work around structures. He credits this to a thinning program that community leaders put in place decades ago. Ruidoso has a fire ordinance that requires all residents and landowners to thin the natural spaces around their homes and businesses to reduce the likelihood of fires spreading, either up or out. In most of the village, the South Fork burned as a ground fire with relatively low flame lengths, allowing firefighters to save numerous homes. However, firefighting personnel still had to contend with extreme weather, a wind-driven flaming front, and the ember storm which preceded the flaming front, with some saying that embers the size of basketballs landed on porches, roofs, and throughout the community.

After evacuation orders were lifted, village leaders started looking around at which houses survived and which burned. They noticed that most of the houses that burned didn’t meet home hardening recommendations. Some had wooden fences that caught on fire and were connected to a wooden deck or some part of the structure that was flammable, causing the fire to spread to the house. There were a lot of homes that use railroad ties in landscaping or as supports under decks, or that had fabric cushions on porch furniture - those ties and cushions caught on fire during the ember storm, which then spread to the house. Even with the ordinance in place requiring residents to thin around their houses, not everyone was following the rules or hadn’t done the work to protect their houses from embers through home hardening. When homes did survive, it’s because they were hardened from embers and flames and the neighborhood vegetation was mitigated (defensible space and forest thinning).

The village is one of the only places in New Mexico with a fire preparation ordinance, so Dick believes that community level preparation made a big difference. 95% of properties in the village have been thinned to get into compliance with the ordinance, with properties being revisited every 10 years to ensure they stay in compliance. The intent of these rules is exactly what Dick saw happen in real time - putting the fire on the ground and preventing it from climbing back into the crown.

Dick believes that the work would have been a lot more effective if the area around the Village of Ruidoso had been treated in a similar fashion. However, the County, which has jurisdiction over the surrounding communities, doesn’t have a similar fire ordinance, and forest treatments on the surrounding National Forest System property were patchy, leading to a mosaic of thinned and unthinned land in the greater Ruidoso area. While each individual subdivision needs to do the work together, they also need to work with surrounding communities to create a cohesive landscape of fire prepared homes, businesses, and wild areas.

Hear about Ruidoso’s efforts from Dick and learn more about safety ordinances, Home Hazard Assessments, and fire preparedness in this archived webinar from Fire Adapted New Mexico.

A neighborhood saved: Circle Oaks, CA, 2017

Cheryl Lynn de Werff was certain her Napa County house was going to burn when she was forced to flee as a massive fire sped toward her Circle Oaks community. It was 1 a.m. and she had just gone to sleep in her second-story bedroom when a sheriff’s deputy pounded on her door. “I came running to the door and he says, ‘Get out! Get out now, there’s a fire coming!’” de Werff recalled. Over the next few days, the Atlas fire burned more than 51,000 acres, killed six people and destroyed more than 300 homes. A week after the community was evacuated, de Werff and her neighbors got the best kind of news possible: all of their homes were safe (Los Angeles Times).

United Policyholders looked into what saved this community when so many others in the surrounding area burned during a rash of intense fires in California’s North Bay in summer of 2017. They concluded that “Circle Oaks in Napa, though evacuated, was largely spared alleged ‘due to vigorous fire prevention programs conducted by residents.’” Several contributing factors aligned to spare the community:

In 2005, a law spurred a change to the Cal. Pub. Res. Code sec. 4291, changing the defensible requirement from 30 to 100 feet. According to CalFire, “proper clearance to 100 feet dramatically increases the chance of your house surviving a wildfire. This defensible space also provides for firefighter safety when protecting homes during a wildland fire.”

The community had spent years installing fire breaks and brush clearance on public land near neighborhoods, which helped to slow the fire.

Neighborhood Ambassadors leading the charge

Firewise Resident Leader! FAC Leader! Spark Plug! Firewise Ambassador! Road Ambassador! Fireshed Ambassador! Neighborhood Ambassador! Volunteer neighborhood leaders who lead wildfire preparedness in their neighborhoods and beyond, regardless of their name or title, can provide great benefits. A wealth of knowledge, skill, tools, and social capacity exists within most neighborhoods, official or not, and working within Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) neighborhoods are a critical scale to improve fire outcomes. Residents in many WUI neighborhoods see firefighters and professional foresters as reliable sources of information; however, these professionals have limited capacity and must focus in high-risk areas where their efforts are likely to yield results. Enter the neighborhood ambassador - because neighbors notice what their neighbors are doing and will often listen to them as sources of information and ideas.

In 2012, the 10,000+ acre Weber Fire blew through a wilderness study area and into the canyon of a neighborhood where wildfire preparedness was being supported through neighborhood ambassadors. The residents’ defensible space and roadside thinning enabled firefighters to protect every structure and build a fire line along their dead-end road and defensible spaces, a feat which would not have been possible a few years earlier. “We ALL had been collectively thinking about THIS fire for a long time. I have told many people that there have been a lot of dedicated folks who have been fighting this fire in their mind, on paper, and on the ground for a decade or more,” wrote Philip Walters, Wildfire Adapted Partnership Neighborhood Ambassador.

Read the full article from 2020 to learn about the origins of the FAC Ambassador Guide, the role that FACNM played in its creation, the importance of neighborhood ambassadors, and real-life examples of neighborhood organization leading to better fire outcomes.

Additional Resources

Upcoming Events

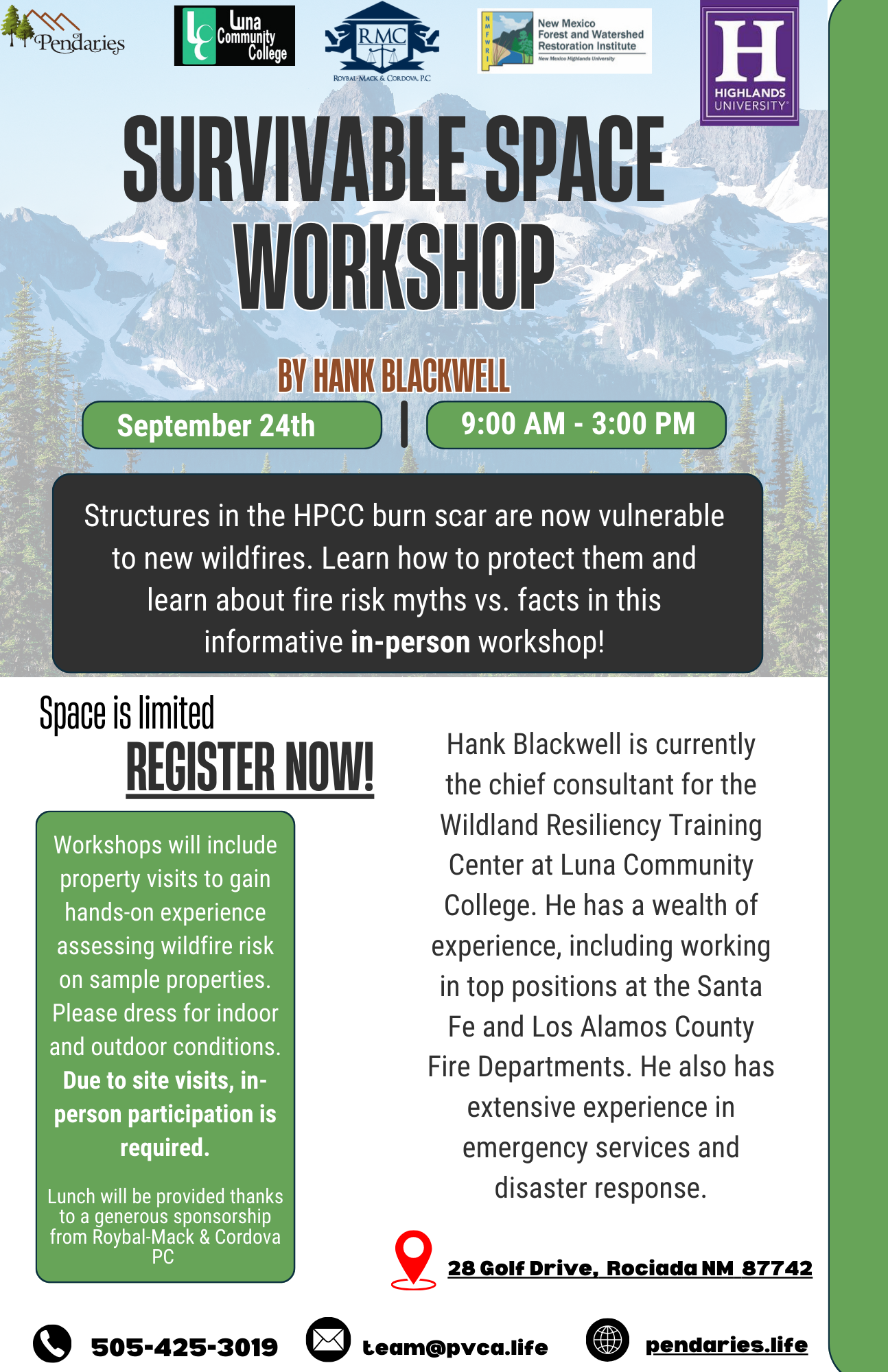

September 24th, 9:00am-3:00pm MT; Rociada, NM: Survivable Space Workshop

It is hard to imagine the possibility of more fires within the HPCC burn scar, but we know it is a reality. What are some simple ways to reduce wildfire risks to homes?

Hank Blackwell, chief consultant for the Wildland Resiliency Training Center, will lead a workshop teaching attendees how to protect structures in the HP/CC burn scar that are now vulnerable to new wildfires. Learn about fire risk myths vs. facts at this in-person event which will include property visits to gain hands-on experience assessing wildfire risk on sample properties.

Space is limited, register now! To learn more, email team@pvca.life or call 505-425-3019.

………………………………….

In the News

Navigating wildfire smoke damage: Insights from the 2021 Marshall Fire

Catrin Edgeley | Northern Arizona University

Dr. Cat Edgeley is a natural resource sociologist interested in social components of forest management. As a wildfire social scientist, she conducts research about how human communities adapt to wildfire. In this presentation she shares research on navigating smoke damage after the Marshall Fire.

………………………………………

Practitioner Paper: Prescribed Fire Planning and Implementation Capacity of Non-governmental Organizations

In 2022, the U.S. Congress made historic investments in wildfire and fuels management through passage of the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Researchers from the Public Lands Policy Group at Colorado State University recognized that federal agencies need a better understanding of the community-based capacity available to support and implement prescribed burn projects if they hope to be successful in strategically deploying these funds across ownership boundaries and at scale (i.e., a large enough spatial extent to achieve fuels and fire management objectives). Additionally, there are many unknowns with how the widespread loss or unavailability of prescribed fire insurance policies has affected prescribed fire practitioners and will therefore affect prescribed burn operations in the future.

To answer these questions and inform effective policy solutions for prescribed fire challenges, the PLPC conducted a national online survey for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who plan, support, and conduct prescribed fire. They had four goals in mind when designing and conducting the survey:

Describe the organizations that support, plan, and/or implement prescribed fire in the U.S.

Identify their capacities and resource needs.

Gauge how they may be impacted by the current scarcity of prescribed fire insurance.

Determine how federal resources could be invested to support these organizations’ workforce.

The resulting report finds that NGOs across the West are generally well set up to conduct outreach to landowners, residents, and natural resources practitioners, to administer grants and manage funds, and assist with or lead prescribed fire implementation. There is room for improvement with educational programming, outreach to disadvantaged communities, outreach to Tribal governments, providing trainings and technical support, and improving direct community outreach before and after burns. The report’s key recommendation for scaling and supporting grassroots prescribed fire efforts in the West include:

Establish dedicated and long-term funding streams to provide security for partners to offer training and support capacity building.

Improve the availability and quality of prescribed fire/smoke liability insurance.

Enhance and invest in prescribed fire workforce Invest in a national prescribed fire claims or catastrophe.

Invest in a national prescribed fire claims or catastrophe fund for third parties negatively impacted by prescribed burn activities.

Identify and support opportunities to reduce implementation barriers related to air quality and waether.