Hi! I am Maya Hilty, a new Fireshed Coordinator with the Forest Stewards Guild. In this role, I support the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition; conduct home hazard assessments; facilitate fuels reduction projects on public and private lands; and grow our Fireshed Ambassador program, where neighbors influence neighbors to make communities better prepared for fire. I will also be contributing to Fire Adapted New Mexico Learning Network into the future, including authoring Wildfire Wednesday blog posts.

Hello Fireshed community,

As of today, almost 28,000 firefighters across the U.S. are battling 95 large fires burning over 3,400 square miles.

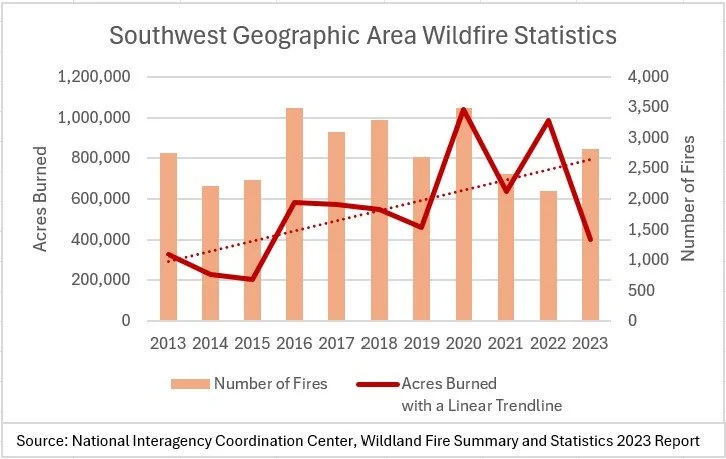

For the past five years, an annual average of ~59,100 wildfires, including both natural ignitions and human-caused fires, have burned almost 12,000 square miles across the nation each year. That includes roughly 2,800 fires per year in Arizona and New Mexico – more than 7 ignitions per day on average, if the fires were spread evenly throughout the year – which have burned 1,150 square miles, or approximately the size of Bernalillo County, annually.

Many of us take for granted that, where fires ignite, firefighting resources will quickly follow. However, for reasons explored below, those resources are stretched increasingly thin during severe fires or during the most fire-prone times of the year.

This Wildfire Wednesday features an overview of the wildland fire workforce, including:

Best, Maya

The Wildland Fire Workforce: A Who's Who

From the local to federal level, here’s who fights wildfires.

As outlined by the Santa Fe County Community Wildfire Protection Plan as well as U.S. Forest Service and Department of the Interior materials, the wildland firefighting workforce includes responders at the:

Local level. This includes, for example, the Santa Fe city and county Fire Department Wildland Divisions.

State level. The New Mexico Forestry Division created two full-time crews in 2024 and trains additional firefighters for hire in an emergency. The Division also collaborates with a state prison in Los Lunas to run the Inmate Work Camp Program, through which the state hires four to six crews of people who are incarcerated to respond to wildland fires alongside other professional firefighters.

Federal level. This year, the federal wildland firefighting workforce includes roughly 11,300 firefighters in the Forest Service and 5,750 firefighters employed by four agencies in the Department of the Interior: the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service and National Park Service. Half the federal wildland firefighting workforce is only employed seasonally, for a maximum of six months, according to data from 2022.

In 2023, costs to suppress and contain wildfires amounted to nearly $3.2 billion in federal firefighting costs alone. Still, the Forest Service, which employs most federal wildland firefighters, needs more funding to meet their capacity needs to address the “ongoing wildfire crisis,” agency leaders say.

Firefighters have a wide range of specialties, from members of handcrews and hotshots, who construct and patrol firelines; engine crews; smokejumpers, who parachute out of airplanes to reach fires in remote areas; helitack crews, who reach fires by helicopter; equipment operators; dispatchers; and other support staff. For more info, visit this Forest Service webpage about firefighting jobs.

Collaboration is key

Thanks to mutual aid and joint powers agreements between tribes and local, state, and federal government agencies, the geographically closest firefighting forces often respond to the initial report of a fire regardless of their jurisdiction over where the fire started.

Firefighting agencies also share an Incident Management System that enables initial responders to more seamlessly scale up a response. In northern New Mexico, that usually means soliciting help from a Southwest Area Incident Management Team.

If a wildfire grows beyond the capability of teams in the Southwest Area (one of 10 wildfire Geographic Area Coordination Centers across the U.S.), the Boise, Idaho-based National Interagency Coordination Center assumes responsibility for mobilizing more resources from elsewhere across the nation. Because there is often a greater need than there is availability of firefighting personnel and equipment, the National Multi-Agency Coordinating Group comprised of state and federal fire management leaders ultimately oversees where to allocate firefighting resources.

In addition, the United States has ever-evolving agreements with Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico and Portugal that enable the countries to share firefighting personnel and equipment. The U.S. considers requesting international help when ~60% or more of domestic wildland firefighting personnel are committed to fires, and the U.S. has received assistance in the form of aircraft or up to 600 personnel from Canada, Australia or New Zealand most years over the past two decades, as detailed in this 2022 paper in the journal Fire.

Challenges in Wildland Fire Management

"Over the last few decades, the wildland fire management environment has profoundly changed. Longer fire seasons; bigger fires and more acres burned on average each year; more extreme fire behavior; and wildfire suppression operations in the wildland urban interface (WUI) have become the norm.” ~ U.S. Forest Service

Growth in fire seasons and severity

Due to factors including climate change, fuel build-up from fire exclusion, and expansion of the wildland-urban interface through continued construction of the built environment in previously undeveloped areas, wildfires have become larger, more severe, and more destructive. For example, the land area in the U.S. burned annually by wildfire has doubled over the past 20 years. Meanwhile, fire seasons have become longer – more than 80 days longer in the western U.S. – straining seasonal and regionally shared firefighting resources.

“We all recognize now we have a fire year, but we continue staffing for a fire season,” fire managers reflected in a review of the destructive 2022 Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire.

Resource strain and scarcity

As we transition out of the months traditionally considered the Southwest fire season – from April to July, when monsoons typically begin – more state and federal firefighting resources will flow to California and the Northwest, and fewer will be readily available to county and community fire managers in the Southwest.

Changes to the workforce

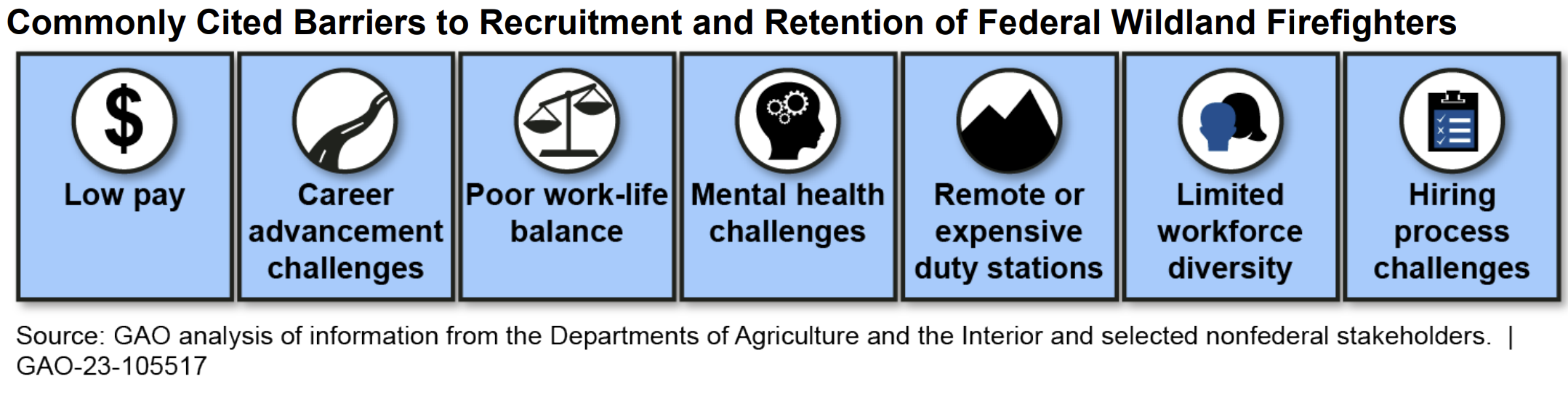

Agencies of varying sizes across the country are struggling to retain and recruit firefighters. In March, the investigative news organization ProPublica reported that the Forest Service has had an attrition rate of 45% of its permanent staff in the past three years. ProPublica and other news outlets reported several factors contributing to attrition in the Forest Service, including low pay, with starting wages of $15 per hour that do not reflect the demands of the job; inadequate attention to physical and mental health problems faced by firefighters; and the growing difficulty of the job as severe fires and extended fire seasons translate more frequent deployments.

A 2022 Government Accountability Office report similarly identified low pay as the primary barrier to the recruitment and retention of federal wildland firefighters, among other barriers such as a poor work-life balance; mental health challenges; and limited workforce diversity.

Enacted and Proposed Policy Changes

“The existing wildfire management system has not kept pace with demands.”

Bolstering the wildland firefighting workforce

Federal agencies have made some headway in recent years to address challenges facing the wildland fire workforce, including raising the pay of wildland firefighters. In 2022, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law raised the minimum wage of federal wildland firefighters from $13 to $15 per hour and provided firefighters with a temporary pay increase of at least $20,000 per year, which lawmakers extended through September 2024.

For the upcoming FY25 fiscal year that begins October 1, the Biden administration has proposed a permanent pay increase for wildland firefighters, along with investments in firefighter mental and physical health and increases in the number of permanent (rather than seasonal) positions. Those proposals are currently making their way through Congress.

A 2023 update to the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy recommended additional solutions, such as ensuring that recruitment efforts reach firefighters of diverse backgrounds and identities. In 2022, 84% of federal firefighters were men and 72% were White. Increasing the representation of women and marginalized groups will not only make the wildland firefighting world more just but will grow the dwindling applicant pool for firefighting positions.

As outlined in the national strategy, the nation ultimately needs a larger permanent firefighting workforce to tackle the year-round work of wildfire mitigation, preparedness, prevention, and postfire recovery, in addition to what we typically think of when we hear wildland fire workforce: wildfire response and containment.

Additional Resources

For more information about the rewards and challenges of a career in wildland firefighting, check out this Preparedness Guide for Wildland Firefighters and Their Families from the National Wildfire Coordinating Group.