As monsoonal rains impact the Southwest, post-fire debris flows and flooding are a major and ongoing concern for those affected by and adjacent to the recent South Fork and Salt Fires. Visit Wildfire Wednesday #138 for information and links to support the community.

Happy Wednesday, Fireshed Coalition community!

Over the past year, news about advancements in wildfire protection and hazard reduction has been coming out faster than most of us can keep up. One common theme that runs through all of the new research is the emerging importance of approaching fire adaptation from a community, rather than an individual, perspective. From the 2018 fire in Paradise to the 2023 fire in Lahaina, this community of practitioners is seeing, in real time, the shift from wilderness wildfire to urban conflagrations.

Today’s blog focuses on resources from organizations such as the Institute for Business and Home Safety which can help residents, neighborhoods, communities, and cities better align their fire preparedness efforts with the latest science.

This Wildfire Wednesday features:

Living with Wildfire

Additional Resources

Living With Wildfire

Challenges across the American West

Wildfire disasters occur when wildfire flames and embers enter communities and destroy hundreds or thousands of homes. Multi-billion-dollar property losses in single wildfire events have become recurrent in the American West over the past three decades. An estimated 45 million residential buildings across the US are at risk of destruction from wildfires. This is a result of a combination of factors, including:

Historic population growth

Unregulated building in wildfire-exposed areas

Overgrowth of forests and rangelands

The effects of climate change

These disasters affect not only lives and property, but the safety and effectiveness of the fire service, the ability of businesses and local governments to recover, and the insurance industry’s ability to provide a financial safety net that makes it possible for people to rebuild their lives and livelihoods.

In a new report from the Institute for Business and Home Safety and National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), some key findings from an investigation into fire vulnerability of communities and measures of wildfire readiness in the WUI include:

Few states and counties with the greatest risk of wildfire disasters are using sound regulatory approaches backed up by consistent enforcement. Outside of California and Utah, there are no enforced, statewide codes addressing wildfire exposures to residential and commercial property; code use and enforcement at the local level remains limited.

The separation of wildfire safety elements from traditional building codes has resulted in limited use by state and local officials. This includes the absence of clear guidance on how such elements can be integrated into building codes. At the state-level, New Mexico has a state-wide and enforced building code, but elected to exclude any WUI code provisions.

A majority of counties and local communities largely fail to address wildfire risks to life and property in a comprehensive manner. These stand in sharp counterpoint to the few local jurisdictions have taken proactive approaches across a range of wildfire safety concerns.

Despite incentives to financially support wildfire mitigation and response capabilities in areas adjacent to national forests and rangelands, one in four high-risk counties have no Community Wildfire Protection Plans (CWPPs), while 17% of counties have not updated their plans in over ten years.

Data on fire service capability, response, and outreach activities in the wildfire arena is difficult to obtain and is highly variable in its form. These inconsistencies make it difficult to compare or evaluate the effectiveness of these activities in a meaningful way.

While local fire departments serve as a vital and trusted communications link for communities to understand how to reduce risk, support for inspection and outreach programs is highly variable across the West because local fire departments often lack both trained staff and financial resources.

There is no correlation between the amount counties spend on wildfire related activities and the use of WUI codes or community wildfire preparedness plans in those counties. Put simply, the investment of public dollars does not necessarily equate to strong codes or planning efforts.

Defining Wildland Fire vs. Wildfire Driven Urban Conflagrations

According to a recent public safety blog from ESRI, wildland fire refers to fires within natural landscapes such as forests, grasslands, and other undeveloped areas. These regions play a crucial role in ecosystem health, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration. However, when fires ignite within these wildland areas, they pose significant threats to nearby communities, infrastructure, and lives.

The distinction between wildland fire and urban conflagration lies in their context: wildland represents the untouched natural environment, while urban conflagration signifies an uncontrolled fire that spreads rapidly through communities. A recent article available on USDA’s website, “WUI Is Not a Wildland Problem,” emphasizes that these urban conflagrations present unique challenges requiring tailored solutions beyond traditional risk reduction, mitigation, and firefighting approaches.

Policy lessons for improving wildfire readiness

According to Living with Wildfire, policymakers at all levels should work to establish much greater levels of wildfire readiness by:

Using and enforcing the most recent model WUI codes for new residential and commercial construction.

Requiring frequent updates of community wildfire mitigation plans.

Incentivizing and encouraging wildfire risk reduction activities at the parcel and community level.

Providing firefighters with the training, equipment, and other resources they need to be safe and effective in response, and serve as a valuable source of education for their communities

What can be done to improve readiness?

Resources for Home and Business owners and community planners

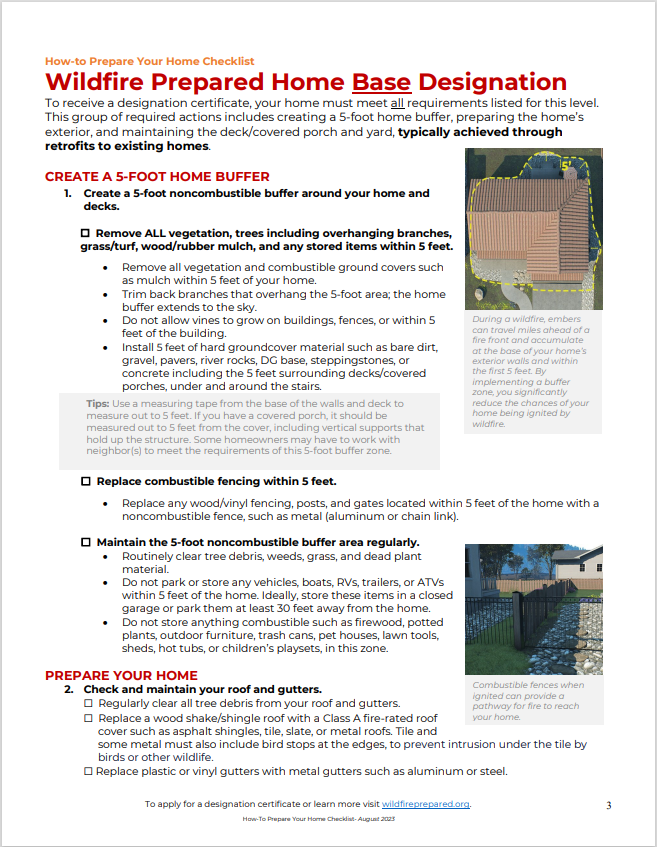

Wildfire researchers at the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) have spent years researching wildfire through both field and lab studies. Now, in collaboration with other wildfire community experts, IBHS has identified the mitigation actions critical to reducing your wildfire risk. While we can’t stop wildfire, there are some steps from the Wildfire Prepared Program that can guide you through required actions to help protect your property. For those who are interested or who require one for insurance purposes, the program provides a pathway to receive a wildfire prepared designation certificate.

The program offers step-by-step instructions for where to start with your home or business preparation process, including a checklist of preparatory items that correspond to different levels of designation (Base, Plus, etc.).

For those seeking a Wildfire Prepared designation, the program provides a quiz to ensure applicants are familiar with the Homeowner Guide and taken the steps necessary for their home to meet all the requirements of this program before paying the application fee for an inspection. This increases the chances of properties passing inspection and being properly designated.

Keeping your designation comes with the requirements of an annual review and a three-year recertification.

The Southwest Fire Science Consortium and Arizona Wildfire Initiative have produced a fact sheet, adapted from the National Volunteer Fire Council - Wildland Fire Assessment Program training course, with a plethora of resources for learning about and protecting your home from wildfire. They suggest starting with a home hazard assessment to determine your wildfire weak points and opportunities for improvement, prioritizing you hazard reduction options, creating a list of all the steps involved to get to a point of being fire prepared, and identifying potential evacuation options as part of your Ready! Set! Go! preparation.

Additional Resources

Understanding community acceptance of fuels treatments

“Public support is crucial for successful fuels management, but vocal opposition can mask broader yet quieter community acceptance. It is helpful for land managers to have a picture of all perspectives, not just the most vocal ones. And what do communities think about fuels treatments? To answer this question, researchers from Rocky Mountain Research Station (RMRS) and Wildfire Research (WiRē) considered data about public acceptance of fuels treatment from studies of 13 communities in the Western US.”

Key findings and management implications of the study included:

Surveys of 13 communities at risk of wildfire showed that public acceptance varies not only across types of fuels management practices but also by community.

Planning and implementation of fuels treatments can benefit from understandings of public acceptability.

Systematic social surveys can provide managers with representative data to complement existing methods for gathering public comments related to acceptance of fuels management projects.

Detailed data can show not only who accepts or doesn’t accept fuels treatment, but whose acceptance could shift towards support or opposition, providing a fuller picture.

Understanding the fuller picture can provide the opportunity for managers to be more strategic with communications and engagements.

Fire in the desert: an overview of a changing landscape

In the hot shrub-dominated deserts of southern New Mexico and Arizona, unprecedented large-scale fires in recent years have been driven by the exponential expansion of introduced invasive plants. A new fire mosaic is being established in the region whereby wildfires can spread from fire-prone forested mountains to the desert valleys, and vice versa, carried by greater connectivity of invasive grass patches. In the Sonoran Desert and other mid-elevation shrublands, an ecological transition from desert scrub to grassland has begun, which creates management and societal challenges as fire becomes a part of the ecology.

Increased urbanization at foothill elevations put tens of thousands of residents and billions of dollars of infrastructure in the wildland-urban interface (WUI) in jeopardy. The increasing likelihood of the alignment of fire-ready conditions (dry fuels, low relative humidity, wind) that can lead to loss of life and infrastructure in the Sonoran Desert at a scale similar to that seen in the 2023 Lahaina, Maui wildfire. To boot, the cost of wildfire mitigation and control efforts available today is orders of magnitude smaller than the economic impact of the grassification of the foothills ‘viewsheds’ and recreation areas, meaning that mitigation is actually cheaper than the true cost of doing nothing. In this report from the Southwest Fire Science Consortium, the authors summarize the history and trends of fire and discuss future conservation strategies.

In determining what land managers can do, the report provides a management toolbox specific to fire in the desert:

Fuel break methods for the desert

Wildfire operation tactics for the desert

Identifying and protecting refugia

Fuels control

Public policy

Restoration