Wildfire Wednesdays #105: Fire Prevention vs Fuels Reduction

Hello and happy Wednesday, Greater Santa Fe Fireshed community!

Fire management comes with a vast vocabulary of unique or unusual terminology. For individuals who are not exposed to these terms every day, exact definitions and usage can be pretty confusing. Having a clear understanding of terminology is important for cross-disciplinary discussion, public education, and to foster a common understanding of what goes into fire management. Today we will be distinguishing between and delving into two sides of wildfire management - fire prevention and fuels reduction.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features:

The fire management triangle - before and during a fire

Differences between fire prevention and fuels reduction

Common questions and misinformation

Be well and stay warm,

Rachel

The Fire Management Triangle

What is wildland fire management?

Colorado State Forestry defines fire management as the “activities concerned with the protection of people, property, and landscapes from [severe] wildfire and the use of [ecologically appropriate] burning for… forest management and other land use objectives, all conducted in a manner that considers environmental, social and economic factors.”

At its core, fire management describes all potential actions for controlling or guiding when, where, and how a wildland fire burns. It takes into consideration what ‘values’ would be at risk were a wildfire to burn through a given area, the ecological impacts of wildfire, and the human factors involved - from ignition to suppression to post-fire recovery.

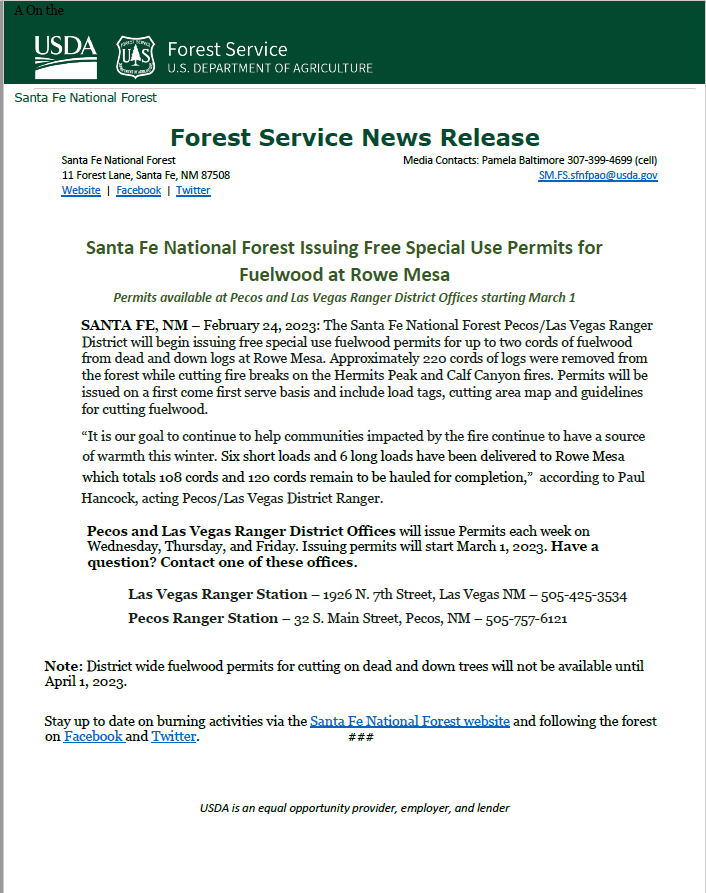

Fire management activities include: pre-suppression, readiness, fuels management, training, prevention, suppression, prescribed fire, fire analysis and planning, rehabilitation, public affairs, and other beneficial efforts. These activities generally fit into two categories - pre-fire and during fire - and can be broken into three distinct branches: fire prevention, fuels reduction, and fire suppression.

What tools do we have?

Fire prevention, or the activities associated with reducing unplanned human-caused ignitions, and fuels reduction, or the management of organic fuels through removal or modification, are generally implemented before a wildfire happens. Fire suppression, or the containment and extinguishing of a fire, is implemented as a wildfire is burning.

Fire prevention: Activities intended to reduce the incidence of unplanned human-caused wildfires [and the risks they pose to life, property or resources], including public education, law enforcement, personal contact, and other actions taken to reduce ignitions. (NWCG Glossary of Wildland Fire)

Fuels reduction: Manipulation, including combustion, or removal of fuels [vegetation and organic debris] to reduce the likelihood of ignition and/or to lessen potential damage and resistance to control. The act or practice of controlling flammability and reducing resistance to control of wildland fuels through mechanical, chemical, biological or manual means, or by fire in support of land management objectives. (CSFS Forestry & Wildfire Glossaries of Terms)

Wildland fire suppression: An appropriate management response to wildland fire that results in curtailment of fire spread and eliminates all identified threats from a particular fire. All wildland fire suppression activities provide for firefighter and public safety as the highest consideration, but minimize loss of resource values, economic expenditures, and/or the use of critical firefighting resources. (NIFC, Wildland Fire Management Terminology)

Distinguishing Between Fire Prevention and Fuels Reduction

Both involve pre-fire work, so what is the difference?

Fire prevention

Wildfires are started either by natural causes (usually lightning) or by human activity. People start wildfires in a wide variety of ways: vehicle exhaust pipes, cigarette butts, poorly extinguished campfires, burning debris piles, and sparking equipment such as chainsaws are all common causes. Other human-caused ignitions come from arson, fireworks, powerlines, and more. With nearly 90% of unplanned ignitions being started by humans, simply reducing the spark can make a big difference in reducing unwanted wildfires.

Fire prevention, which focuses on stopping a fire before it starts, is accomplished primarily through education. Research has shown that human ignitions tend to be clustered, or occur most commonly, around cities, roadways, and busy recreation areas such as trailheads and campgrounds. Fire prevention efforts seek to inform the general public of the ways in which fires are started, the impacts of those fires as they burn, and how they can be prevented. In general, prevention programs most likely to be effective are those that give people information and tools that enhance their perception of their power, as individuals, to prevent wildfires.

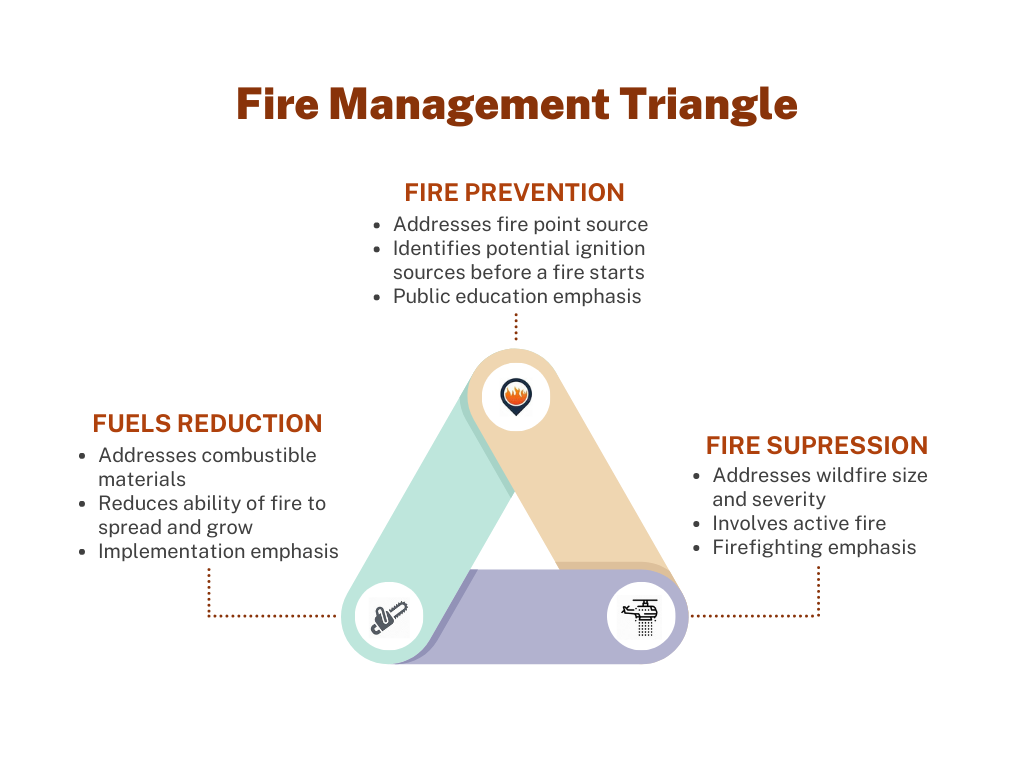

Read more about fire prevention in the 2018 report on reducing human-caused ignitions in New Mexico, a 2021 report on investing in wildfire prevention, the DOI’s 10 tips to prevent wildfires and NM Forest Division’s fire prevention tips.

Fuels reduction

“When vegetation, or fuels, accumulate, they allow fires to burn hotter, faster, and with higher flame lengths. When fire encounters areas of continuous brush or small trees, it can burn these ‘ladder fuels’ and may quickly move from a ground fire into the treetops, creating a crown fire… [The objective of fuels reduction] is to remove enough vegetation (fuels) so that when a wildfire burns, it is less severe and can be more easily managed.” (NPS, What is Hazard Fuel Reduction)

Fuels reduction aims to thin out living and dead vegetation from forested areas to reduce the total amount of fuel that is available for a fire to burn. It also is designed to create breaks in the fuel type and arrangement (e.g. reducing ladder fuels) so that even if a fire starts, it cannot quickly move from the ground level into the tree canopy. These goals may be accomplished through ecologically-based forest thinning (the mechanical removal of shrubs and small trees), mastication, chipping, and prescribed fire (the purposeful introduction of fire under favorable conditions).

Fuels reduction is not intended to stop the forward progress of a wildfire as soon as it hits the treatment area; instead, fuels reduction treatments are designed to reduce the growth of fires that ignite in treated areas, moderate fire behavior by reducing crown-to-crown movement when a flaming front encounters a treated area, and enable fire management activities (containment and suppression) by giving firefighters a safe space to directly interact with the fire.

Wildfire ecologists almost universally support fuels reduction — especially in forests that used to flourish under frequent ground fires, such as the ponderosa pine forests of the Southwest. Fuels reduction is also an effective pre-fire treatment in wildland-urban interfaces and in home defensible spaces. Read more about fuels reduction in the High Country News article, Does thinning work, a Forest Service article on thinning the forest for the trees, and an NPR interview with UNM professor Matthew Hurteau.

Continuing the Conversation

Common questions and misinformation

Still have questions about fire management and what can be done to prevent or control a fire before it happens? Refer to the resources below for more information.

Revisit our September 2022 blog post on counteracting wildfire misinformation, which includes examples of common ecological restoration myths and the facts to correct them.

Read 10 common questions (and their answers) on adapting western US forests to climate change & wildfires.

Review an ERI working paper summarizing key insights on the 18th - 21st centuries’ unprecedented, human-caused fire exclusion and its impacts on fire-dependent forest landscapes in western North America

Scan the Western Environmental Law Center’s fact sheet on 8 key points to adapting forests to wildfire and climate change.

Wildfire Wednesdays #104: Asset-Based Community Development

Hello Fireshed Community,

Each community or neighborhood across the Santa Fe Fireshed has a unique set of strengths and and challenges. These unique characteristics are what gives our communities identity. Many of us are proud of where we are from or where we live because of these local identities. As we work towards a more fire adapted future, it is important that we work with the strengths and challenges of our individual communities rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach. This process takes time and local leadership, but it leads to better outcomes in the end. This week’s Wildfire Wednesday will focus on Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) to support local leaders in working documenting their community’s strengths and challenges in hopes of working with them. This framework is brought to us from the national Fire Adapted Communities learning network (FAC Net) and the Fire Learning Network.

This Wildfire Wednesday includes:

New Mexico Counties Wildfire Risk Reduction grant funding announcement

Information on Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD)

Information about Upcoming Events

Community Resiliency Fairs - Mora, Las Vegas, Buena Vista, Sapello, and Chacon

SW Tribal Fire & Climate Virtual Workshop

Stay Safe,

Gabe

Asset-Based Community Development - Overview

Asset-based Community Development (ABCD) is a specific path for identifying and connecting a community’s assets so that they use and grow their capacity to change on their own terms. “Community” can refer to a neighbor-hood, a village or district, a residential development or a town—an area that residents recognize as “theirs.” Asset mapping is used in ABCD in a facilitated, participatory and inclusive process through which a group of residents identify the individual, associational and institutional assets in their neighborhood or community, then use them in envisioning and taking practical steps toward community improvement. The group usually produces a map (that locates assets geographically) or an inventory (that lists assets in a document or database). Either of these should be a “living document”—periodically updated to include new people, associations and institutions and their assets.

In this blog post, we share an abbreviated set of steps for ABCD to serve as an introduction to the framework. For the full guide on Asset-Based Community Development, click here to explore FAC Net’s full page of community engagement resources, including the whole ABCD series.

What Do Community Assets Look Like?

Community assets are usually identified according to the following three categories because each type has different kinds of assets, all of which are important.

Individual assets are skills (machine repair, emergency response or bookkeeping), talents (music, baking, note-taking) and abilities (listening, physical strength, inclusivity).

Associations are any informal, voluntary group of residents. Their assets might include local knowledge and traditions, communication and networking, and event organization.

Institutions are formal organizations with employees and buildings. Their assets might include professional contacts, meeting space, employment opportunities and equipment.

How Do You Start?

Telling stories in a small group is a good place to begin. Ask questions like these—“What are good community experiences that we have had in the past? What do we already have that works well? Why does it work well?”—and notice the people, places and organizations that come up. The fun and meaningful work of identifying the assets you already know of, and engaging with others to discover their assets, leads to exploring potential interconnections. Connecting assets creates excitement and new possibilities, opening opportunities for new relationships and new action.

For a full overview, click here.

Asset-Based Community Development - Next Steps

Situation Assessment

Situation assessment is Step 1 in an Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) process that helps people connect their strengths to create new opportunities for living well where periodic wildland fires are expected. Situation assessment is a good place to start if you do not already have partners in the area where you will be working. It allows you to learn directly from community members about their strengths and challenges. It also gives you a way to identify people who enjoy meaningful community involvement and who are natural collaborators. Once you have people to work with, you will be ready for Step 2 in asset-based community engagement: asset mapping with community “connectors.”

Steps for a Sitiuation Assessment

Define the task but be flexible.

Set a geographic boundary, a period of a few months, and a target number of interviews. Plan time before and after interviews to explore the area and chat with store owners, restaurant waitstaff, librarians, artists and others about their experience of fire.Use the “snowball” method.

Start with just a couple of key contacts instead of a complete list. End each interview by asking who else you should talk to.Welcome different types of fire-related experience and interest.

Look for and welcome diverse opinions and expertise. You may learn as much from a rancher, a school administrator and a bicycle race promoter as from a battalion commander and a forest health activist.Consider where to meet, for how long.

Expect to spend about an hour per interview, so meet someplace comfortable. Conference rooms are likely to emphasize professional position while restaurants offer a more social feel.Ask questions, don’t discuss.

Focus on understanding your interviewee without adding your own commentary. Ask clarifying questions, but do not correct any misconceptions about fire at this point. Instead, learn about why and how they came to their present understanding.Take notes.

Hand-written notes tend to seem less intrusive than a recording app. Just note down the story outlines and the assets mentioned—any individuals, groups or organizations that are described positively. Stop taking notes if a story becomes personal.Start as you mean to continue.

Focus on the positive (asking questions about assets and not getting bogged down by problems), send thank-you notes, and keep personal information confidential to set up good working relationships for the future.

For a full description of the situation assessment process, click here.

Asset-Mapping with Connectors

Identifying Connectors in Your Community

Connectors should be people who are interested, and perhaps experienced, in some aspect of wildland fire preparedness, response or recovery. But they need not be professional experts or recognized leaders. Connectors may be a retired Forest Service archeologist, someone from a small college, a mental health counselor, a chef, the owner of a small farm, and so on. Shared interest in fire may bring them together, but their social smarts make them successful at mobilizing the community’s fire-related assets

The Process

Invite the connectors together in a comfortable, informal environment—a restaurant or library, or at a kitchen table. Tell each other stories about what you care about related to fire, and why. The community’s problems and opportunities will naturally arise. Facilitate the conversation by writing down all assets, the individuals, groups and organizations that are mentioned positively.

Ask the connectors to collaborate with their acquaintances to identify more of the community’s fire-adaptive assets. Reconvene on a schedule that works for everyone to share what you are finding and the ideas that are emerging.

Capture the assets simply and easily on a community asset map or inventory; ensure that it is shared with everyone who participates and is updated frequently.

Enjoy! As people recognize their community’s strengths, project ideas will flow. Focus on enabling the creativity that occurs, rather than limiting the scope of imagination to existing programs or plans. The connectors will work within the community to devise opportunities for people and organizations to contribute what they do best. Down the road, the experienced fire practitioners located through asset-mapping will help ensure that more ambitious projects are safe and consistent with best practices.

For more information on asset-mapping with connectors, click here.

Wildfire Risk Reduction Grant Funding - New Mexico Counties

The New Mexico Association of Counties is pleased to announce the 2023-2024 Wildfire Risk Reduction Program for Rural Communities that assists at-risk communities throughout New Mexico in reducing their risk from wildland fire on non-federal lands.

Funding for this program is provided by the National Fire Plan through the Department of the Interior/Bureau of Land Management for communities in the wildland urban interface and is intended to directly benefit communities that may be impacted by wildland fire initiating from or spreading to BLM public land.

Grant funding categories include:

CWPP Updates up to $20,000/project

Education and Outreach Activities up to $15,000/project

Hazardous Fuels Reduction Projects up to $75,000/project

Project proposals require a minimum 10% in-kind cost share and must be completed within the 12-month award timeline of July 1, 2023 - June 30, 2024.

Applications are due to the local BLM field office for signature(s) by Friday, March 3, 2023, and the completed application(s) with all signatures are due to NMAC by 5:00 p.m. Friday, April 7, 2023. Please contact Aelysea Webb at (505) 395-3403 or awebb@nmcounties.org for more information.

Upcoming Events and Offerings

Community Resilience Fairs

SW Tribal Fire & Climate Virtual Workshop

February 10 -- February 24 -- March 10 (2023)

9-11am MST | Zoom

Please REGISTER - click here

Goal: Increase tribal capacity around wildland fire and climate change impacts across the Southwest.

Participants: Tribal fire and natural resource professionals and non-tribal professionals that support tribal fire and climate resilience. Please share with others who may have interest.

Topics (based on participant interest):

Indigenous perspectives and resources on fire, climate change & adaptation

Identifying capacity needs and partnership options for managing wildland fire in the face of climate change (including MOUs and other agreements

Opportunities and challenges with burning (permitting, burn plans, cultural burning, cross-jurisdictional coordination, etc.

Hazard response (FEMA, public safety, emergency operation plan/management) and risk reduction

Post-fire: restoration, flooding, and economic impacts

Expanding an ongoing conversation & support network

Assessment and monitoring of actions and strategies

Other interests (please share when you register - see link above)

Format: Virtual (Zoom) will enable greater participation across the Southwest landscape. Each tribal-led workshop session will include a mix of topical presentations and peer learning and exchange.

Cost: Free

Glorieta Camps Prescribed Burning to Continue as Soon as January 24

Glorieta Adventure Camps, The Nature Conservancy’s Rio Grande Water Fund, and the Forest Stewards Guild will continue to take advantage of favorable weather conditions in the Santa Fe area for winter pile burning at Glorieta Adventure Camps. This prescribed burn is part of Glorieta’s long-term commitment to improve forest health and reduce the wildfire hazards. The objectives and collaborative commitment of this burn align with the mission and vision of the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition.

Individuals with respiratory health concerns or smoke sensitivity can borrow a HEPA filter for the duration of burn-related smoke impacts through a Filter Loan Program supported by the Coalition.

An Effort Highlighted: The Albuquerque Journal

The Glorieta Pile Burn, which was initiated last Thursday, January 19, after the Camp received 6-8 inches of snow from a winter storm, was one of the State’s first prescribed fires since last year’s Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fire. The cooperative effort was featured in Sunday’s edition of The Albuquerque Journal. “This is the first burn of the season for the Forest Stewards Guild in a year where both public and private crews are approaching prescribed burns with extra caution”. Full coverage of crew precautions and what the organizations are trying to accomplish with this burn can be found on the Journal’s website or by clicking on the image.

Questions about the burn may be directed to Eytan Krasilovsky, Carlos Saiz, or Sam Berry with the Forest Stewards Guild.

Wildfire Wednesdays #103: Community Wildfire Protection Plans

Hello and happy Wednesday!

In autumn of 2022, the US Forest Service announced the creation of Community Wildfire Defense Grants (CWDG). This funding is intended to help at-risk local communities and Tribes plan and reduce wildfire risk by prioritizing at-risk, low-income, disaster-impacted communities. A key requirement for CWDG eligibility is the possession of a Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) for the intended geographic area. For communities just beginning the process of wildland fire hazard planning, creating a CWPP can act as both a roadmap for action and a huge first hurdle to getting started.

This week’s blog offers resources to learn about the history of CWPPs, the key elements for inclusion in a plan, suggestions for forming a collaborative and jumping into the CWPP writing process, and an invitation to attend a CWDG listening session to learn about and inform future CWPP implementation funding opportunities.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features information on:

CWPPs: the basics

A listening session series on CWDG funding

The FAC NM spring webinar series, beginning today (1/18) at 2pm MST!

Upcoming webinars from the SW Fire Science Consortium

Take care and stay warm,

Rachel

Community Wildfire Protection Plans

Where it began: the Healthy Forest Restoration Act

In 2001, the National Fire Plan legislation brought renewed focus on engaging communities in federal wildfire mitigation efforts. As a result, the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003 (HFRA) directed the Secretary of Agriculture (National Forest System lands) and the Secretary of the Interior (Bureau of Land Management lands) to plan and conduct hazardous fuel reduction projects on Federal lands. HFRA focuses attention on four types of land:

The wildland-urban interfaces (WUI) of at-risk communities,

At-risk municipal watersheds,

Where threatened and endangered species or their habitats are at-risk to catastrophic fire and where fuels treatment can reduce those risks, and

Where windthrow or insect epidemics threaten ecosystem components or resource values.

The legislation contains a variety of provisions aimed at expediting the preparation and implementation of hazardous fuels reduction projects on federal land and assisting rural communities, States and landowners in restoring healthy forest and watershed conditions on state, private and tribal lands. Through this language, the bill encourages communities to go through the collaborative process of planning, prioritizing and implementing hazardous fuel reduction projects, ultimately resulting in community wildfire protection plans (CWPPs) to reduce their wildland fire risk and promote healthier forested ecosystems.

Communities who have developed CWPPs have done so using many different processes, resulting in plans with varied form and content. Due to the vagueness of the legislative language, communities have the freedom to develop CWPPs that are relevant to their local conditions and allows for the development of resource capacities that communities are using to produce diverse plans that build on local context to achieve broad policy goals of wildfire hazard reduction.

Read a summary of implementation actions enabled through the HFRA and how the bill’s language has enabled flexibility with authoring and customizing CWPPs.

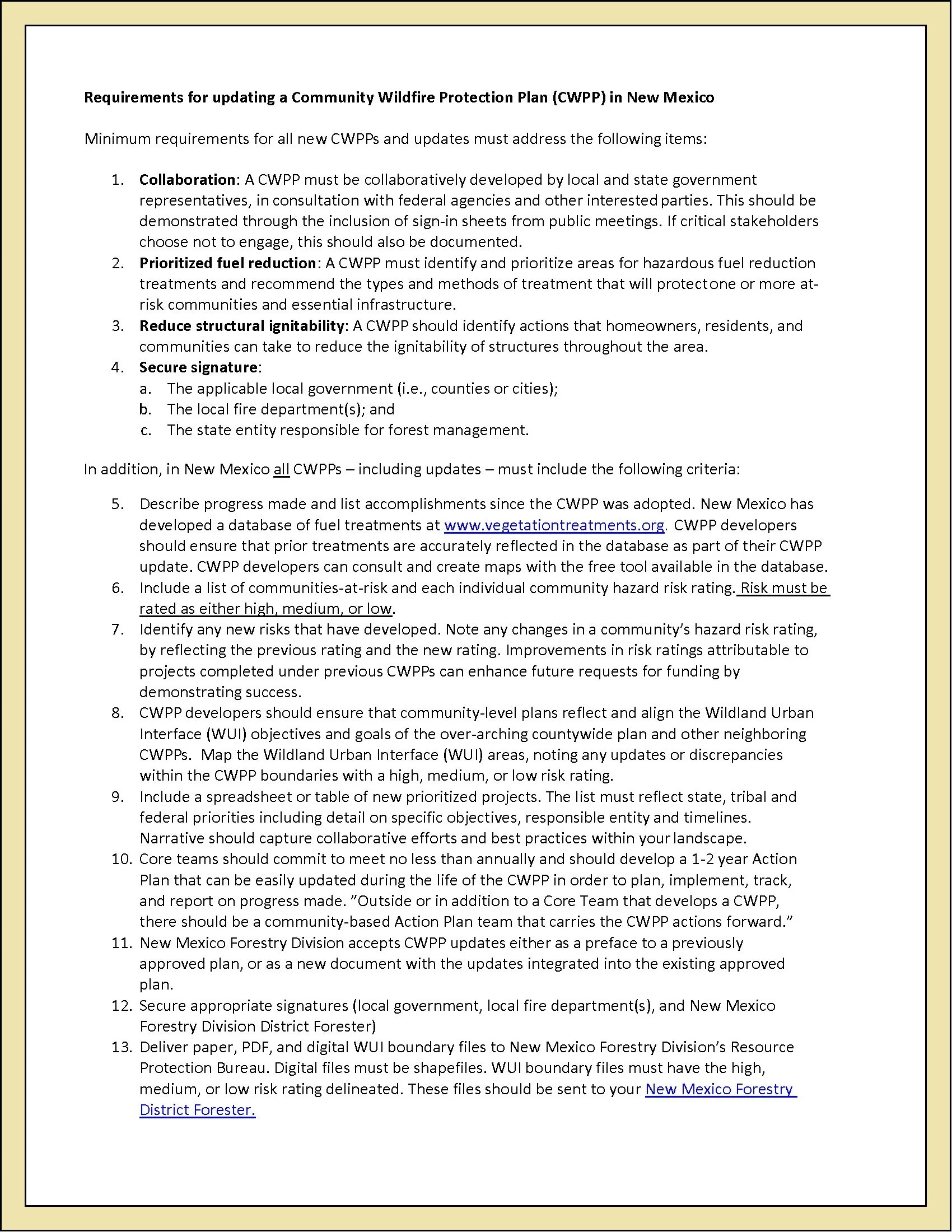

Elements of a Community Wildfire Protection Plan

“Community Wildfire Protection Plans have become the primary mechanism for evaluating risk due to their emphasis on community involvement and assessment of local resources. CWPPs are also an important planning document used by emergency responders and citizens to plan for and respond to wildfire emergencies. Local leaders and governmental entities find CWPPs valuable for the purposes of identifying critical needs and prioritizing funding” (NM EMNRD, 2021).

A CWPP has five main sections:

Community Risk Ratings

Priority Fuel Reduction (vegetation treatments)

Priority Actions (evacuation planning, education outreach, etc.)

Reduction of Structural Ignitability

Adoption and Signatures

Community Risk Ratings

Risk ratings are specific to distinct communities. They are usually calculated using a computer-based (GIS) wildfire risk model and must be categorized as either high, medium, or low. Models may include a number of different risk factors, each given a weight which corresponds to their importance, such as:

Fuel hazards (vegetative fuels present)

Risk of wildfire occurrence (locations of previous wildfires)

Essential infrastructure at risk (homes, businesses, power, communication facilities, etc.)

Other community values at risk (areas with scenic, recreational, economic or cultural value)

Local preparedness and firefighting capability (road access, distance from fire stations, distance from water sources)

Where appropriate, these ratings should reflect and align with national Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) objectives and goals.

Priority Fuel Reduction

A CWPP must identify and prioritize areas for hazardous fuel reduction treatments and recommend the types and methods of treatment that will protect one or more at‐ risk communities and essential infrastructure. This identification will likely be based on a combination of community risk ratings and social and economic values (tourism hot spots, areas of cultural importance, business hubs, etc.). Prioritizing fuel reduction creates a collaborative map for which areas will receive treatment in what order and why.

Priority Actions

After identifying the areas at greatest risk and greatest need for action, the next step in developing a CWPP is to select community wildfire risk reduction priorities. These actions may include fuel treatments, restoration projects, outreach and education, evacuation planning, and more.

Reduction of Structural Ignitability

In additional to priority fuel reduction projects and risk reduction priorities, a CWPP should identify actions that homeowners, residents, and communities can take to reduce the ignitability of structures throughout the area. This part of the plan may include guidelines for home hardening, creation of defensible space, and funding mechanisms for this work throughout high-priority communities.

Adoption and Signatures

The HFRA requires local governments, local fire department(s) and the state entity responsible for forest management (EMNRD) to sign off on the final contents of a CWPP. Additional signatories on your CWPP may include collaborators involved in the creation of the plan and key individuals from communities which will be impacted.

Other important CWPP elements may include a 1-2 year Action Plan, accomplishments since the last CWPP (for plan updates), and WUI Mapping, Hazard Mapping, and lots of spatial analysis.

Upcoming Opportunities

Spring FAC NM Webinar Series

Fire Adapted New Mexico is kicking off its spring webinar series with an informational presentation by Gabe Kohler of the Forest Stewards Guild on FAC NM’s new membership structure.

January 18 @ 2pm MST: Revitalizing Membership in FAC NM

An interactive webinar on the network’s revitalized membership structure and improved tools, resources, and facilitation for peer-to-peer knowledge exchange. This presentation will cover new levels of involvement in the learning network, upcoming workshops and grants available to members, and future plans for network growth and other continual learning opportunities.

Keep an eye on the FAC NM Events webpage for announcements and registration for our mid-March and mid-May webinars!

Community Wildfire Defense Grant (CWDG) Webinars

What: The CWDG Program will conduct a series of Listening Sessions to solicit feedback and comments on the program and provide opportunities to share recommendations for how to improve CWDG in the future.

When: January 18th, 19th, 20th and 26th.

There are Listening Sessions scheduled for each of four Notice of Funding Opportunities, but you may to attend whichever Listening Session suits your schedule.

Sign up through the Wildland Fire Learning Portal by enrolling in the 2023 Community Wildfire Defense Grant (CWDG) Listening Sessions course, or visit this link: https://wildlandfirelearningportal.net/course/view.php?id=1908

Southwest Fire Science Consortium Monthly Webinars

January 31 @ 3pm MST: Wildfire and Climate Change Adaptation of Western North American Forests: A Case for Proactive Management

Three experts will tell the story of forest change since colonization, and share insights and answer questions about how we might steward a legacy of forest change and mitigate climate change impacts. Following their presentations, the speakers will lead a discussion on reframing management direction and current barriers to increasing the pace and scale of forest adaptation.