Happy Wednesday, Coalition Members and Partners.

As our communities strive to recover from the impacts of recent wildfires and continue to make incremental progress toward risk reduction from future wildfires, we recognize the ongoing importance of knowledge sharing. Workshops, webinars, trainings, and other tools enable us to work together toward a Fire Adapted New Mexico. FACNM is taking a break from our usual Wildfire Wednesday structure to provide information on upcoming opportunities which align with this commitment to learning.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features information on:

Free post-fire land restoration workshops

Webinars from the Southwest Fire Science Consortium

Women in Wildfire Training through the US Forest Service

Wildland Urban Fire Summit call for presentations

Funding opportunity: Community Wildfire Defense Grants

Best wishes,

Rachel

Wildfire Response and Recovery in New Mexico

Post-Fire Land Restoration Workshops

Luna Community College and the NM Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute at Highlands University are partnering to offer two one-day workshops to help landowners with tips and techniques for reducing erosion and restoring forests in burned areas.

Enroll on-site to learn how to manage, treat, and utilize burned forested lands.

Saturday, August 20 at 8:00am at the Rociada Fire Station

Saturday, September 10 at 8:00am at the San Geronimo Fire Station

For more information, contact Karen Wezwick at (505) 454-5308 or email at kwewick@luna.edu

Southwest Fire Science Consortium

Upcoming webinars

Wednesday, August 31 at 1:00pm MDT - Post-Fire Logging in Southern Colorado: Changes to Post-Fire Recovery

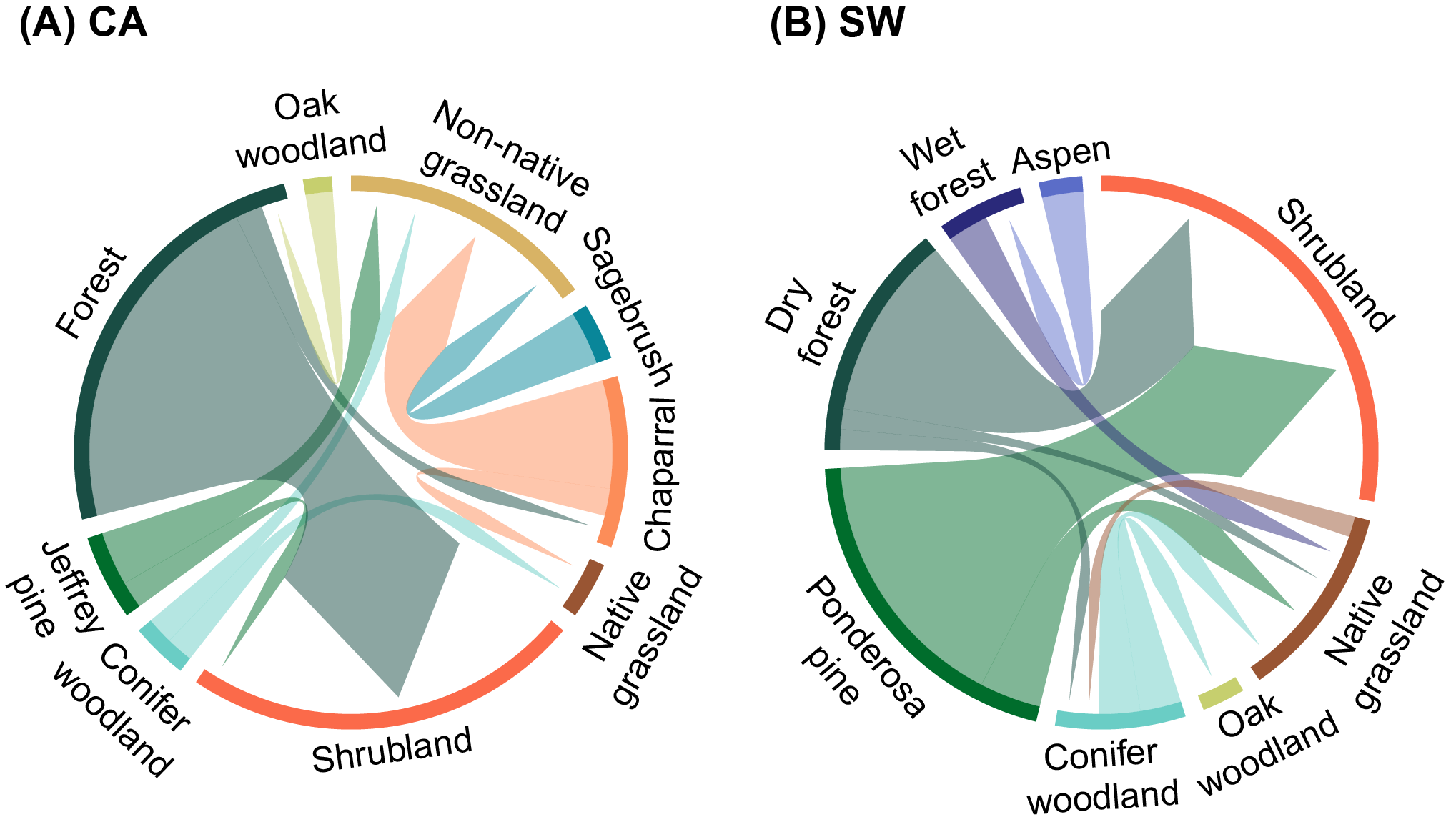

Following a wildfire, successful tree regeneration is mediated by multiple factors, from the microsite to landscape scale. This presentation demonstrates the importance of microsite conditions such as soil moisture and temperature in predicting conifer tree establishment and the impact that post-fire salvage logging can have on these conditions.Wednesday, September 21 at 12:00pm MDT - Vegetation type conversion in the US Southwest: Frontline observations and management responses

Ecosystems of the western U.S. are experiencing vegetation type conversions (VTC) in response to land-use change, climate warming, and their interactive effects with wildland fire. This presentation discusses VTC challenges, management responses, and outcomes from the collective experience of managers, scientists, and practitioners across the southwestern US.

Women in Wildfire

Training opportunity in Lakeside, AZ

The Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests will be hosting the annual Women in Wildfire Training this fall. This is a fast paced, six-day training where women from around the nation have to opportunity to participate in hands-on wildland fire training in a simulated fire assignment. Anyone is welcome to apply, no experience necessary. After the completion of the training, students become certified as FFT2 (Firefighter Type 2) and will be provided with information on how to apply in USAjobs if interested in working on a fire crew.

Time and travel are paid, and equipment is provided.

Where: the Pinedale Work Center on the Lakeside District of the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests.

When: Friday-Sunday, Sept 23-25 and Sept 30-Oct 2; participants must attend both timeframes.

How to apply: visit the wildland fire learning portal by August 21st.

If you have any questions, please contact Naomi Corkish at naomi.corkish@usda.gov / (928) 333-6247) or Matt Sigg at matthew.sigg@usda.gov / (316) 617-9898.

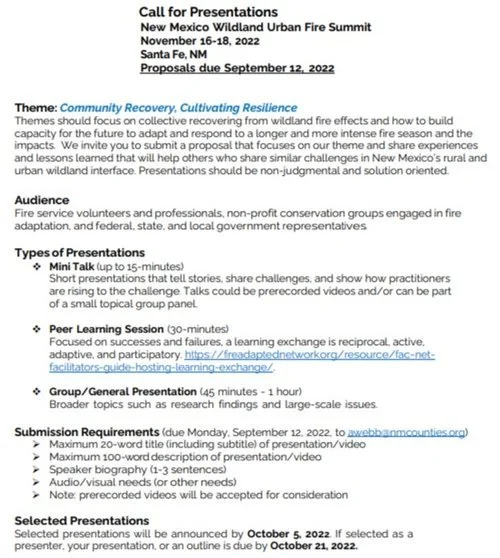

Wildland Urban Fire Summit 2022

Community Recovery, Cultivating Resilience:

Call for submission of presentation proposals!

The New Mexico Wildland Urban Fire Summit invites you to share experiences and lessons learned that will help others who share similar challenges in New Mexico’s rural and urban wildland interface. Please consider submitting a proposal that focuses on this year’s theme: collective recovery from wildland fire effects and how to build capacity for the future to adapt and respond to a longer and more intense fire season and its impacts. Presentations may range from 15 minutes to one hour and should be non-judgmental and solution oriented.

Audience: fire service volunteers and professionals, non-profit conservation groups engaged in fire adaptation, and federal, state, and local government representatives.

Submission Requirements:

Maximum 20-word title (including subtitle) of presentation/video

Maximum 100-word description of presentation/video

Speaker biography (1-3 sentences)

Audio/visual needs (or other needs)

Note: prerecorded videos will be accepted for consideration

All submissions due by Monday, September 12, 2022

For more information, contact Aelysea Webb at NM Counties: 505-310-3564 or awebb@nmcounties.org

Community Wildfire Defense Grants

A primer on preparing to apply

What are Community Wildfire Defense Grants?

The Community Wildfire Defense Grants (CWDG) are intended to help at-risk local communities and Tribes plan and reduce the risk against wildfire. The program prioritizes at-risk communities in an area identified as having high or very high wildfire hazard potential, are low-income, and/or have been impacted by a severe disaster. Applications are due Oct. 7, 2022.

There are two primary project types for which the grant provides funding:

The development and revision of Community Wildfire Protection Plans.

The implementation of projects described in a Community Wildfire Protection Plan that is less than ten years old.

Before proceeding with this grant opportunity, determine if the program is the right fit for your community:

The application must come from a local government, Tribe, non-profit organization (including Homeowners Associations), State forestry agency, or Alaska Native Corporation.

Project work must occur on non-federally administered land. Work may occur on lands held in trust for Native American Tribes and individuals.

The decision tree (left) can help you identify opportunities. Learn more through the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network.

Additional links and resources:

The official USDA Forest Service Community Wildfire Defense Grants webpage.

Documentation of data sources and methodology from the Wildfire Risk to Communities team.

Community Wildfire Defense Grants information (including fillable PDF form) for the Western Region.

System for Award Management (SAM.gov)