Happy Wednesday, and happy official start of summer, FAC NM community!

Our last Wildfire Wednesday issue, #113, introduced the idea of building landscape resilience (ability to maintain ecological function after a disturbance) through large-scale collaborative land management projects. A common theme was that land managers use forestry treatments such as thinning and prescribed fire to support landscape resilience by creating a diversity of forest structures on the landscape. Local research has shown, time and again, that using targeted forest thinning followed by the intentional return of fire to treat an overly thick and unhealthy forest is the most effective combination for establishing landscape resilience in fire adapted ecosystems. Prescribed burning is a key element in guiding watersheds and forests to be more diverse in species, age, and spacing, and better prepared for wildfire, pests, disease, and other disturbances.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features:

A review of the use of intentional fire

Success stories in your backyard

Upcoming events and announcements

Take care,

Rachel

Use of Intentional Fire

A natural history

Many forests across North America but especially in the West “grew up” with fire. Over hundreds of thousands of years, as these landscapes formed, fire was present and endemic plants and animals evolved to be resilient to wildfire (or in some cases, to require it for their reproduction and survival). We refer to these ecotypes as fire adapted forests.

Communities of the Southwest have, in the past, been fire adapted as well. As we discussed in Wildfire Wednesdays #107, humans and our ancestors have been intentionally using fire for more than 400,000 years. Indigenous communities around the world have used fire in ceremony and management of hunting and plant cultivation, and Euro-American colonizer-settlers used fire to clear land around their communities. This use of fire, mimicking or working in tandem with naturally ignited wildfires, kept forests relatively thin and diverse with a mosaic of open meadows, thick groups of trees in drainages and other topographic features which acted as refugia, and less dense forest along slopes and ridgetops. Fire also maintained a diversity of tree ages and plants which grew under the forest canopy or along streams and rivers.

After a century of treating forests as a commodity which needed to be protected from “bad” fire, including demonizing and sometimes criminalizing indigenous and other traditional use of fire, folks across the West have begun to reevaluate this relationship. While farmers and ranchers more or less continually used fire to maintain their land, even when fire suppression was the national policy, it wasn’t until the late 1900s to early 2000s that we saw the reintroduction of fire to forested environments through prescribed and cultural burning. Ryan, Knapp, and Varner (2013) write:

“In North America, recognition of the ecological benefits of prescribed burning was slow in coming and varied geographically. Fuel accumulation and loss of upland game habitat occurred especially quickly in productive southern pine forests and woodlands and ecologists in the southeastern US promoted the use of fire in land management from early on. In spite of their convincing arguments, fire in the southeastern US (and elsewhere) was still frequently viewed as incompatible with timber production due to the potential for injury to mature trees and the inevitable loss of tree seedlings.”

Reclaiming our relationship to fire

Scientific, managerial, and, to an extent, public perception has shifted dramatically over the past 20+ years as we have come to understand what many before us inherently knew: that fire is an integral process for maintaining the integrity, stability and beauty of our biotic communities.

Burning small and burning often in a way which restores forest heterogeneity (diversity of species, age, and type) effectively reduces the density and connectivity of trees within forests and the prevalence of dense forests across landscape. This in turn reduces the severity of subsequent wildfires and makes them easier to manage.

An annual average of 6+ million acres are treated in the U.S. using prescribed fire. According to New Mexico’s 2020 Forest Action Plan, “nearly 5 million acres of forested land need treatment — thinning, prescribed burns or weed management — on a rotating cycle to create resilience to fire. That works out to 300,000 acres a year, a target that the state isn’t even close to reaching” (Searchlight NM, 2022). Despite the challenges and risks, prescribed fire and other means of reintroducing fire to the landscape will need to be part of the solution to this backlog.

Success Stories Close to Home

The Zuni Mountain Collaborative

This story comes to FAC NM from US Forest Service employee Shawn Martin, Silviculturist with the Cibola National Forest.

Where it began

Toward the end of the 1990’s, the Cibola National Forest (CNF) and its partners began to take more interest in managing the Zuni Mountains area as a cohesive landscape. Beginning in 1999, the Forest implemented several projects clocking in at a few hundred acres - the Bluewater Creek Improvement Project, followed by the Bluewater Creek Restoration Project and Bluewater Road Realignment in 2002. Between 2001 and 2003, CNF and Pueblos of Acoma and Zuni applied for and received three Collaborative Forest Restoration Project (CFRP) grants; the Forest Stewards Guild and Mt. Taylor Manufacturing received two more CFRP grants in 2009 and 2010 focused on capacity building, increased forest restoration, and wood utilization.

An integral requirement of these federal grants is collaborating with external partners - with members of nearby communities, local nonprofits and businesses, and various landowners or managers in the area - while planning and implementing the funded forest restoration project. Years later, in 2011, when the landscape applied for a long-term Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP) grant for the Zuni Mountains, these same concepts necessitating collaboration and cooperation would apply.

Scaling up

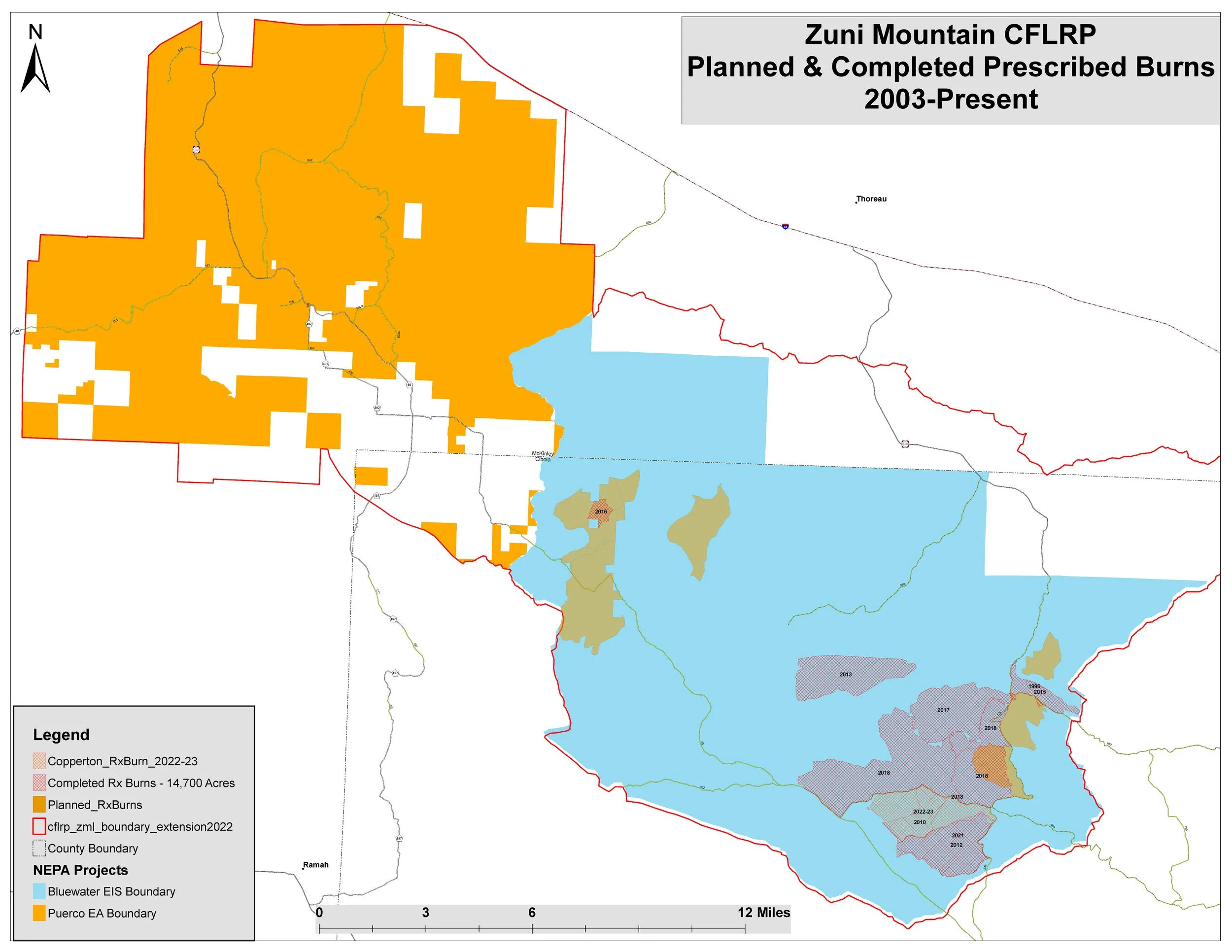

Over the next few years, wildfires across the Southwest and in the landscape, such as the 2004 Sedgwick Fire, began burning hotter, longer, and more acres. These events reinforced the need to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration treatments, invest in ways to utilize wood and establish a forest restoration economy, and create fuelbreaks to protect nearby communities from wildfire. The CNF began surveying larger and larger chunks of land to comply with the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) and funding through the American Restoration and Recovery Act created a new instrument to implement forest restoration activities. Following receipt of 10-year CFLRP funding in 2012, low-intensity prescribed fire was reintroduced with the implementation of the Carbon, Fossil, and Copperton burns.

Prioritizing fire

The 2020 Puerco NEPA decision expanded restoration opportunities beyond just thinning burning to include watershed, wildlife, and range improvements. Treatments have always been prioritized around building and maintaining a restoration economy, so most thinning has been centered around treating overstocked and even-aged stands that were easily accessible and economically feasible for the MTM mill. Prescribed fire has generally followed behind forest thinning, but large areas which are either inaccessible for mechanical thinning (wilderness, far from a road, thinning would be too expensive) or are already prepared for the reintroduction of fire (previously thinned or burned, did not experience the same level of historic fire exclusion) have been identified as “burn only”.

In prioritizing which areas to treat with prescribed fire, managers first considered existing mechanical thinning project plans which they could follow with fire as a secondary treatment. The next logical step in prioritizing prescribed fire treatments was to work out from or expand on that foothold of initial burns. Land managers knew that, in this part of the Southwest, the dominant wind (direction in which the wind blows the majority of the time, having to do with larger atmospheric patterns) came out of the southwest and blew to the northeast. The CNF designed the next decade of treatments, therefore, to a) follow existing road systems for ease of access and b) create a “catcher’s mitt” of restored forest which was treated by thinning and/or prescribed fire and could intercept a wildfire, stopping its forward progress or reducing its severity before it burns into nearby communities to the northeast. Such treatments have proven efficacy, such as the 2013 Rim Fire on the Stanislaus National Forest, just east of California’s Yosemite National Park.

“Even if a previous fire doesn’t stop the subsequent fire, [research] shows that areas recently burned by low to moderate severity fire re-burned at similarly low to moderate severity… In this way, each new reduced severity fire becomes a potential anchor that could be used to limit the spread, moderate severity, and potentially lower the daily smoke emissions of a subsequent fire.”

- Dr. Leland Tarnay, FAC Learning Network, 2018

Medio Fire, 2020

In late August 2020, treatments associated with the Pacheco Canyon Forest Resiliency Project played a consequential role in mitigating the forward progress of the Medio Wildfire burning in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, 11 miles northeast of Santa Fe, NM. These treatments, especially prescribed burns adjacent to a historic fire scar, contained the wildfire and prevented it from burning into and devastating the Santa Fe Municipal Watershed (the source of up to 40% of Santa Fe’s drinking water). Visit the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition webpage or click on the factsheet or video below to learn more about this success story.

Midnight Fire, 2022

The Midnight Fire burned through a section of the Carson National Forest near El Rito in June, 2022. Fire crews and incident commanders feared that the blaze could grow as big or fast as nearby fires (this was burning at the same time as the Hermit’s Peak - Calf Canyon Complex), but previous prescribed burn projects and managed fires helped stymy its forward progress and reduce the burn severity. The region's previous fire and forest thinning acted as "building blocks" to slow the Midnight Fire. Click the image to the right to read more about this success story in a September article by the Albuquerque Journal.

Upcoming Events and Learning Opportunities

Workshops

July 21 and 27, 2023: Community Wildfire Defense Grant Workshops

NM EMNRD - Forestry Division will hold two workshops to help potential CWDG grant applicants review the lessons learned from the first cycle of this program and learn about changes to current processes. This workshop is intended to help strengthen applications in real time, whether applications submitted in the first round did not get funded or individuals are still thinking about submitting an application. Participants should bring their latest revision of their application for review or their project ideas which have not yet been fleshed out into an application so Forestry Division can provide direction and helpful tips for success.

If you are unable to attend either of the in-person meetings and would like to have your application reviewed, you can reach out to Abigail Plecki, Community Wildfire Defense Grant Coordinator, and set up a time to meet virtually (505-231-3086 | abigail.plecki@emnrd.nm.gov).

Webinars

July 25, 2023, 12:00-1:00pm: Increasing Post-Wildfire Planted Seedling Survival

Join the Southwest Fire Science Consortium as Chris Marsh with UNM’s Earth Systems Ecology Lab discusses how consideration of climate trends, microclimatic conditions, topography, and local vegetation influence planted seedling survival and can be used to guide reforestation planning in the Southwest.

Resources in the News

Following the East Coast’s inundation of wildfire smoke from blazes burning in Canada, National Public Radio (NPR) published an article on lessons from the West for dealing with wildfire smoke. While this may be old news to many, the refresher is always worthwhile.

Read it here.