Happy Wednesday, Coalition community.

Language has always fascinated me, especially regional dialects - these variations of the same language that develop over time and differ, sometimes significantly, because they are built by the unique environment, activities, and influence on any one area. Native speakers of the same language may yet encounter a language barrier if they grew up learning different dialects!

The language of wildfire is not so different. Individuals who have been steeped in this terminology are well versed to understand and speak it easily, while ‘fire speak’ can sound pretty foreign and unintelligible to folks who haven’t encountered it before. Today’s Wildfire Wednesday seeks to simplify and explain this language and the way we use it so that we all have access to the same common lexicon, knowing that effective communications build support for sound wildfire policies.

Today’s Wildfire Wednesday features:

Basic fire terminology

Techniques for fire communication

Resources and opportunities

Be well and stay warm,

Rachel

Basic Terminology

Establishing a common vocabulary

Wildfire is our common denominator - regardless of age, background, place, or culture, we all are impacted by it in the Southwest (and increasingly across the country). We may be directly impacted as a fire burns close to our town or indirectly via smoke, the impacts on our loved ones living elsewhere, or the anxiety caused when we hear about it on the news. To understand one another when we talk about fire, from the names we give it (wildfire, managed fire, prescribed fire) to the way we interact with it (suppression, boxing it in, preparing for fire), we must build a shared vocabulary and boil down the technical jargon to find common ground through plain English.

Tools for learning

The first video below provides a basic introduction to terms you may hear in fire management, including ignition source, containment, wildfire versus interface fire, size explanation, control, fire escapes, holding, hot spots, evacuation notices, and more. This video was produced in Vancouver, B.C., so it is worth noting that in the U.S. fires are generally measured in acres; 1 hectare is equivalent to approximately 2.5 acres.

The second video provides a quick introduction to terminology you may hear during an explanation of active wildfire (such as a morning fire briefing), including how to describe behavior and parts of the fire. This includes terms like flanks, fingers, pockets, islands, creeping, running, spotting, fire whirl, crowning, and more. Some of these terms will be used during other types of fire such as controlled burning.

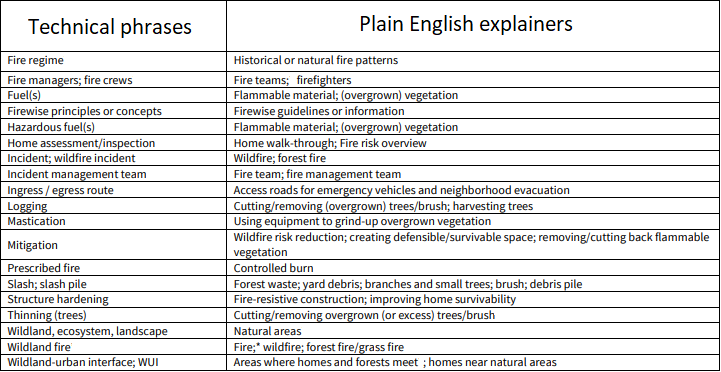

The National Wildfire Coordinating Group also provides an online Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology and the (easier to use) searchable PDF which comprehensively list phrases and acronyms used in federal wildfire management. While this tool is helpful for understanding language used by federal fire practitioners and collaborators, it does not necessarily allow for the two-way construction of shared language with members of the public.

Moving beyond specific words and technical terms for wildland fire, let’s dive into how we talk about fire more broadly.

Techniques for Fire Communication

Building Support for Sound Wildfire Policies through Communication

Think back to a day that you were put in a bad mood because of something someone said to you - it may not have been what they said, but how they said it or the specific words they used that nagged at you. The way that we share and receive information matters, especially about something as emotionally charged as wildfire (and associated land management and community preparedness practices). This section provides some suggestions from the Wildfire Resilience Roadmap about being mindful of our fire language.

Summary: Across the country, a majority of Americans believe that forest health as worsening, and concern about wildfires has been steadily growing even among those not directly impacted. They overwhelmingly support a framework to reduce severe fire risk through improved forest management and the use of intentional fire – support that cuts across geography, party, gender, age, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Research shows that people would rather invest now to reduce severe fire risk than later to address the aftermath of fires, including investments in year-round, trained teams to reduce the risk of severe wildfires. At the same time, innate and growing skepticism about government makes it challenging but important to document these policies’ proven track record and to highlight provisions requiring accountability and transparency in carrying out risk reduction strategies.

Communication Recommendations

These recommendations are taken from Appendix B of the Wildfire Resilience Roadmap and are based on 2022 general public opinion research. See the excerpted PDF here.

Build on growing concern that fires are more severe and more frequent: messaging does not need to persuade voters that a problem exists – rather, it needs to funnel their existing concern into support for action.

Do not rely on concern about wildfire smoke to leverage action: while poor air quality tends to be a concern when and where problems with wildfire smoke are occurring, as the winds shift and fires die down, intensity of concern does as well. Instead, focus on fires themselves.

Do not count on using climate change as a rationale for action: climate change ranks in the middle-tier of a list of factors that the general public believes is contributing to increasingly frequent and severe wildfires. Deep ideological polarization continues to play a substantial role in perceptions of climate change.

Focus on impacts of climate change, most notably the contribution of droughts to the greater frequency and severity of fires: even without explicitly naming climate change as the cause, clearly describe its visible, tangible and current impacts on forests and pivoting to how to help them.

Acknowledge the important ecological role of fire: highlighting the benefits of normal, healthy fire cycles can be helpful.

Stress the need for improved forest management to prepare for fire: there is bipartisan agreement that the current approach to forest management isn’t working and that the overall condition of America’s forests has worsened over the last few years.

Do not ignore the need for more careful public behavior in and around fire-prone forests: many members of the public believe that a large share of wildland fires is started by humans, whether through a discarded cigarette or a campfire left unattended. Have open communication about fire exclusion versus fire suppression.

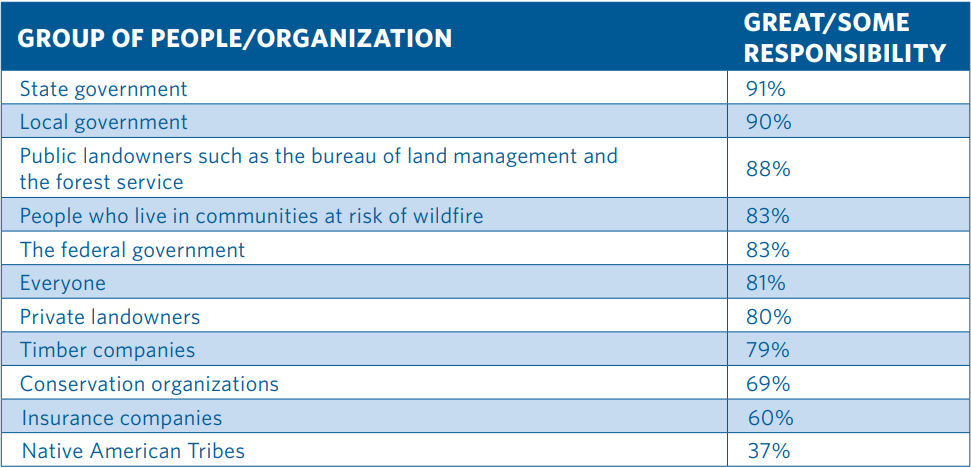

Focus on the role of partnerships in acting to reduce fire risk: every level of government, timber companies, residents of fire-prone areas, conservation organizations, and insurance companies bear responsibility for reducing the risk of severe wildfire.

Use the term “controlled burn”: while it may be considered less scientifically accurate, the general public prefers and better understands the term “controlled burn” in comparison to “prescribed fire.”

Focus on the principle of preparation: we intuitively understand and value saving money and lives by stopping unnecessary fires from happening and ensuring that ones that do occur are manageable and limited in their negative impacts. Contrasting the high financial and emotional cost of in the aftermath of a wildfire with the relatively low cost of intervention before the fact is highly persuasive. “When it comes to reducing wildfire risk, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Highlight the creation and support of a year-round workforce: while wildfires are seasonal, land management is not, necessarily. It makes sense to invest more evenly throughout the year, keeping workers stably-employed, fairly-paid, and connected to the land, than to hurriedly try to assemble a competent workforce as fires occur.

Call out the need to protect and support first responders whose lives are at risk in addressing wildfires: build support for investments in wildfire risk reduction by reminding people that reducing the intensity and severity of wildfires makes a tough job less dangerous and more manageable.

Do not use language focused generally on equity in distributing funds, but instead explain the context: given careful wording, members of the public consider communities with high risk and few resources as a high priority for funding.

Do not focus on investing in protection of timber supplies or recreational areas: these are things that could be restored or recovered more easily if need be than water supply, habitat, or human communities.

Do not rely on the word “resilience” alone: resilience is seen as a quality displayed in recovery after a disaster has struck, rather than one that reflects an ability to avoid its worst harms. Preparation, safety and health are better since they leave open the possibility that a community could avoid the worst impacts of a disaster – rather than conceding that they will occur. Focus on concrete and desirable outcomes, such as “safe and healthy forests” or “fire-prepared communities.”

Do not assume that people understand how fire threatens water supplies - rather, convey the reality and seriousness of the risks: once the process by which fires lead to contamination of survey water is briefly explained, people find it compelling.

Stress provisions for public disclosure, audits, and fiscal accountability in any public spending proposal: in general, we show high degrees of skepticism about “government” writ large. In any discussion of significant federal investment in wildfire risk reduction, that skepticism (and related fears of waste) emerges as the biggest obstacle to winning public support.

Use state and federal agencies with land management responsibility as messengers: people understand federal land managers as being guided by the mission of protecting the health of forests for current and future generations and wildlife, and largely trust information from these groups as being free of a profit motive or ideological agenda.

Give wildland firefighters, park rangers, wildlife biologists and Tribal leaders prominent roles as messengers: we trust messengers who we see as neutral experts on fire issues, such as park rangers, wildlife biologists, and tribal leaders. We also value those with firsthand experience, such as people who have lost their homes to wildfires.

Resources and Opportunities

Webinars

7 December, 2023 at 2:00pm: Supporting Prescribed Fire in New Mexico

Join FACNM as we discuss New Mexico's new certified burn program and ways to responsibly and safely increase implementation of prescribed fire across jurisdictions and land boundaries in the state! This presentation is open to practitioners, leaders, and members of the public. Read more about the new certification program here.

For those interested in getting involved now, the self-paced online training for the New Mexico Certified Burn Manager Program is available, with options for pile burn or broadcast burn certification!

29 November / 14 December, 2023 / 10 January, 2024 at 12:00pm: Developing Community Wildfire Protection Plans in Your Community

Learn what a Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) is and why your community may need one, what the process involves and what the components are, what resources you need to complete a CWPP, how to use CWPPs to support funding for implementation and more! Join the webinar to hear about how CWPPs are increasingly being used to direct various funding opportunities, including Community Wildfire Defense Grants (CWDG). This program will also be offered en español.

Online Portals

One site to access fire resources, news and events, and contacts: the Fire Learning Network (FLN), Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network (FAC Net), Indigenous Peoples Burning Network (IPBN), and Prescribed Fire Training Exchanges (TREX and WTREX) have launched a new website! At firenetworks.org you’ll find information about each of the networks and the way they tackle our fire challenges with unique and complementary approaches to a common goal.

In the News

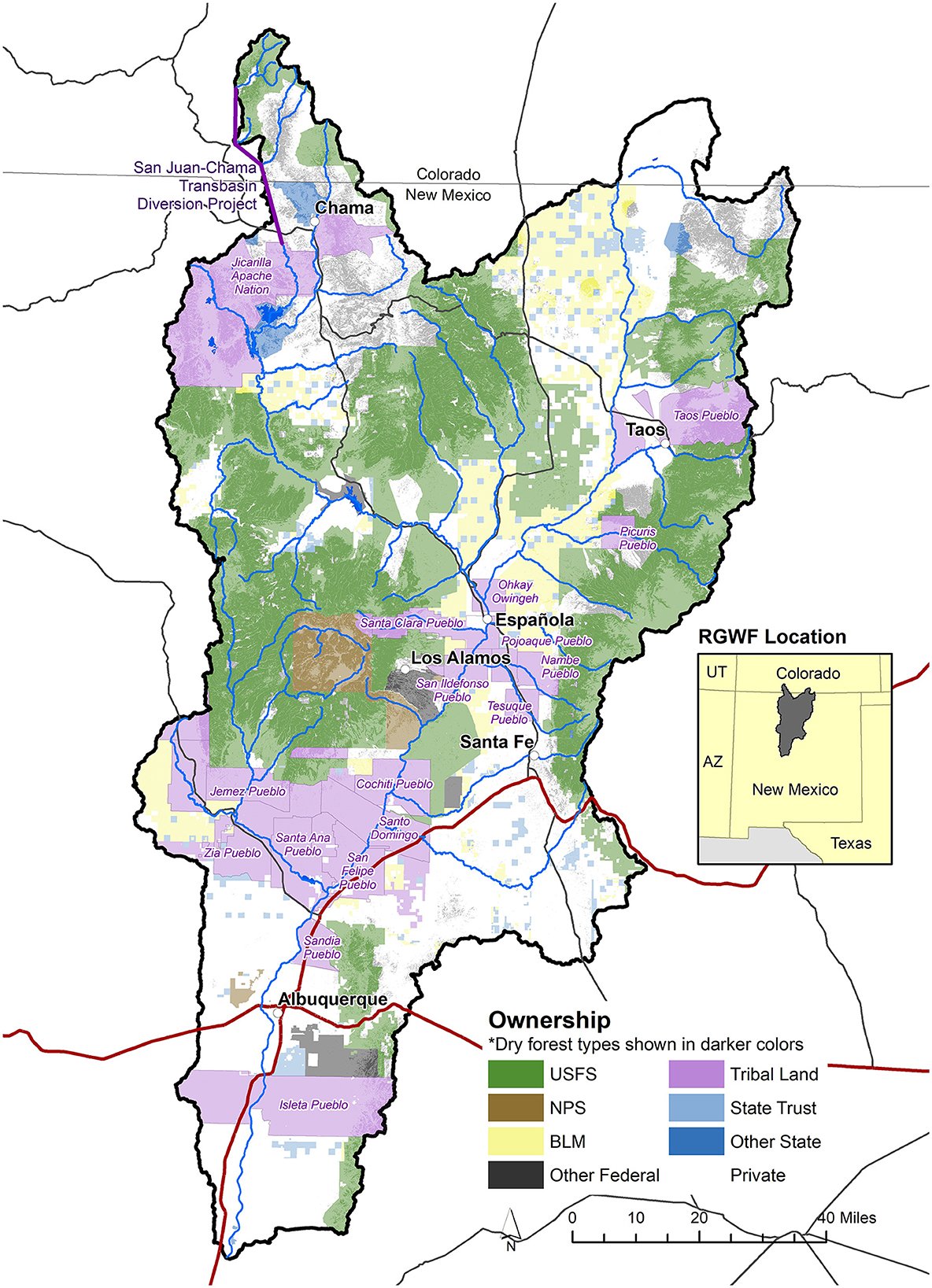

The Rio Grande Water Fund is highlighted as “one example of an emerging adaptation strategy that is working within—and beyond—existing legal and policy frameworks to accomplish more collaborative efforts across jurisdictional lines and administrative barriers” in the Frontiers in Climate article “Adaptive Governance Strategies to Address Wildfire and Watershed Resilience in New Mexico's Upper Rio Grande Watershed.”