Most of us begin our days by driving to school or work, running errands, dropping off and picking up our kids, and gliding through life’s rhythms with the graceful profile of the Sangre de Cristo and Jemez Mountains in the backdrop. This living landscape that we call home surrounds us but may not always be front of mind.

Yet, up in the hills, drainages, mesas, and meadows, teams of land stewards are tirelessly at work to buoy the health and resilience of our forests and wild areas against the impacts of pests, disease, drought, and catastrophic wildfire.

While proposed forest treatments and their associated environmental clearances receive a lot of press, this type of ecological work has a long history in Greater Santa Fe Fireshed. For as long as people have lived here they have altered the land. Over the past several decades, a variety of partners have implemented forest and fuels treatments based on local research across ecotypes and land ownerships. The 2020 Santa Fe Community Wildfire Protection Plan highlights where these treatments have or will happen as well as the science and experience-based recommendations for making Santa Fe a fire adapted county now and into the future.

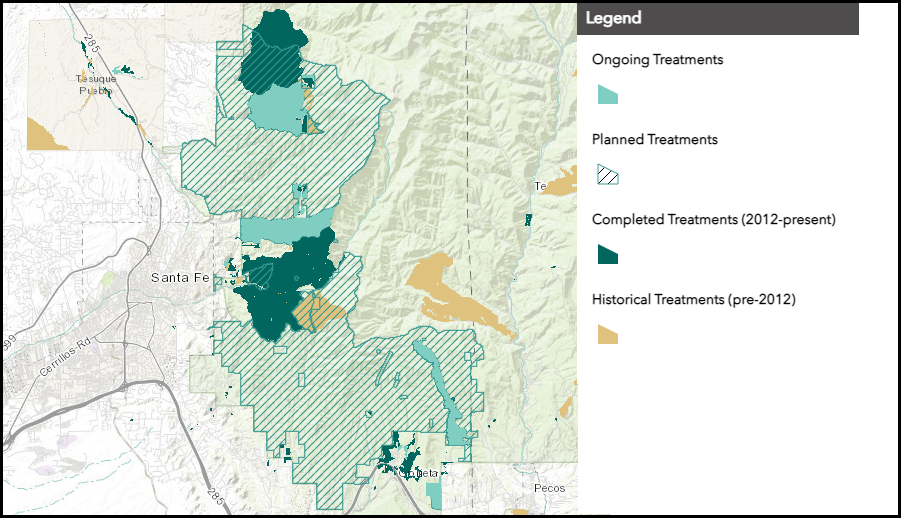

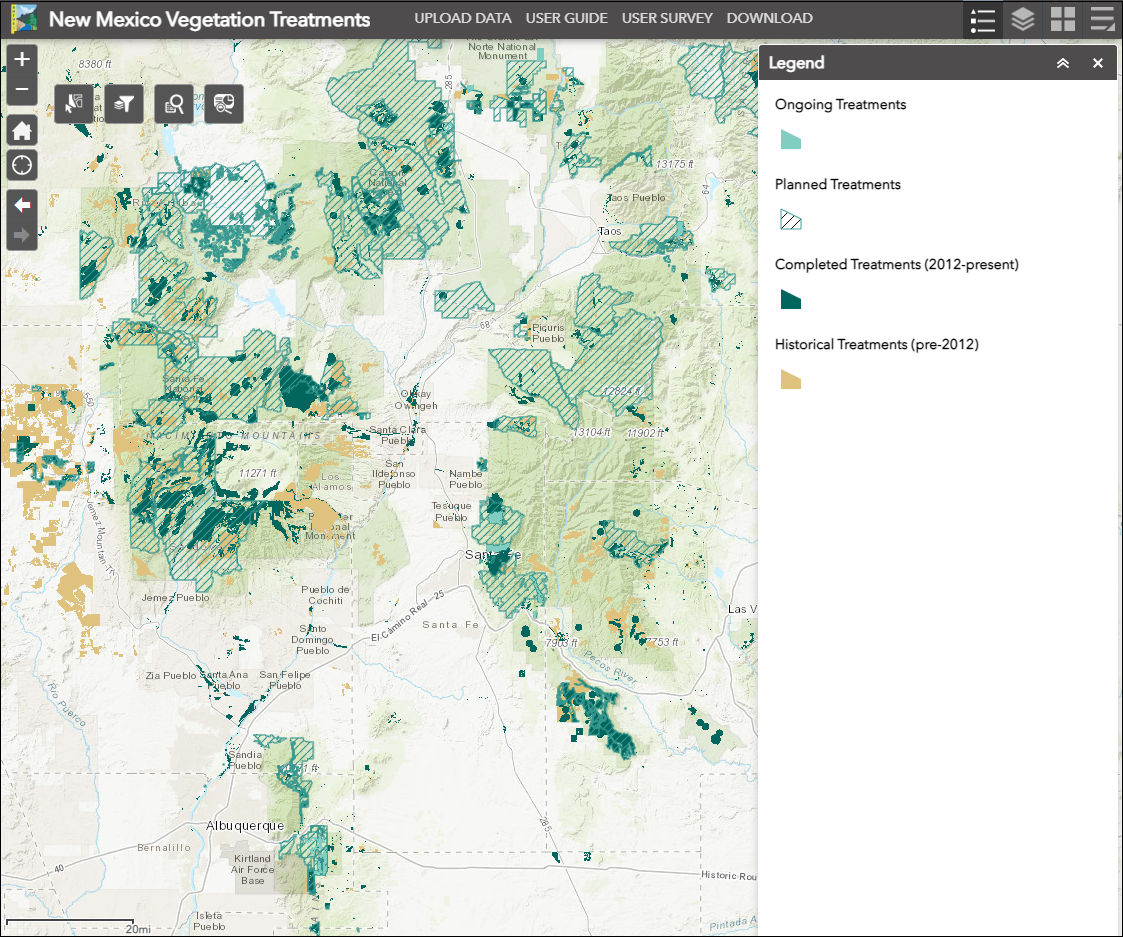

Where are treatments happening?

Based on local science and traditional knowledge, federal agencies, tribes, state divisions, local county and city entities, nonprofits, and private landowners are all playing a role in reducing fire threat, securing water, and protecting our communities.

North of Santa Fe, the Pueblo of Tesuque and partners have worked on implementing a multi-year forest treatment in Pacheco Canyon. The thinning, burning, and slash management work done in this area provided a foothold for firefighters to head off the 2020 Medio Fire and prevent it from burning into the ski basin.

East of Santa Fe, the US Forest Service and collaborators have implemented multiple forest resiliency projects, including in the Gallinas Municipal Watershed WUI and Hyde Park WUI projects. These treatments improve forest health and provide water security for our community by reducing the likelihood of a high-intensity wildfire in the municipal watershed.

The Nature Conservancy manages the 525-acre Santa Fe Canyon Preserve, an area which has received “years of restoration and conservation” to restore its natural ecological function and diversity.

Local landowners have been participating for years in cost-share agreements, city initiatives, and opportunities through FAC NM and FireWise to increase their homes’ defensible space and create a safer and healthier Wildland Urban Interface.

The Santa Fe National Forest is currently revising and preparing to re-release the Santa Fe Mountains Landscape Resiliency Project Environmental Assessment for a period of public scoping and comment. This NEPA document will pave the way for treatments which seek to improve the resilience of a priority landscape to future disturbances by restoring forest and watershed health and reducing the risk for catastrophic wildfire on up to 38,680 acres of federal National Forest Systems land. This project is grounded in the latest research and risk assessments and has the support and collaborative input of a coalition of federal and non-federal partners.

View an interactive map of the state’s historic, completed, ongoing, and planned projects, as well as wildfire footprints and more. This Opportunity Map is provided by the New Mexico Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute (NMFWRI) and housed by New Mexico Highlands University.

Why treat the forest?

When Spanish and other European settler-colonizers arrived in New Mexico, they brought with them large herds of sheep, cattle, and other grazing ungulates. These herds quickly denuded the land, eating grasses and shrubs down to the roots. Without these fine fuels to carry fire across the landscape, lightning ignitions were unable to spread and the region’s natural frequent fire regime was interrupted. The creation of the US Forest Service and federal focus on wildfire suppression further disrupted the fire cycle, and in the century-long absence of wildfire that followed the state’s ponderosa pine and mesic mixed conifer forests grew unnaturally thick and dense.

We are still dealing with the ramifications of our legacy of fire exclusion. These dense forests are more likely to carry high-intensity wildfire with often catastrophic consequences for trees, soils, flora and fauna, and water. Trees have less access to limited water and nutrients as they compete with their overcrowded neighbors, especially in times of drought and environmental stress. The forests are also at greater risk of pest and disease outbreaks, with uninterrupted forest canopy to transport those pathogens, and are less able to fight them off.

Thinning and burning the forest in ways which are safe, effective, and in line with our traditional and scientific knowledge allows land managers and stewards to restore forest resiliency. Practitioners who slowly reintegrate fire into our fire-adapted ecosystems empower them to be prepared and able to withstand the next wildfire. Forest treatments allow us to realign and learn to live with the rhythms of the desert Southwest.

Read more, including a Santa Fe New Mexican article from local ecologists and researchers in support of forest treatments and a release about how land stewards in the northern Gila Mountains are bringing back fire to restore the land.