Happy Holidays, Fireshed Community!

Today’s guest writer, Rachel Bean of the Forest Stewards Guild, joined us back in September to discuss the connection between forest health and healthy water. Click here to revisit that blog post and refresh your memory on the basics of a watershed. Today, Rachel will be examining potential post-wildfire impacts on water.

This Wildfire Wednesday features information on:

Post-fire debris flows

Water-supply reservoir impacts

Water quality following a wildfire

Fire and Floods

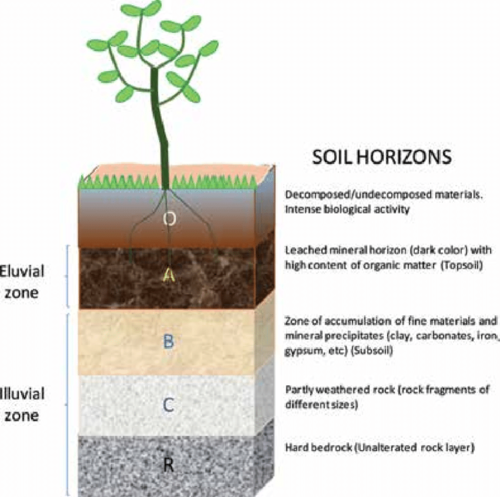

Soil comes in all shapes and sizes. More specifically, soil comes in all different textures (particle size), porosities (the amount of space between particles), and structures (the way particles of different sizes are arranged in layers). The combination of all of these physical factors determines how much water the soil can absorb when it rains or snows and how much water it can hold in the form of soil moisture. A complete soil profile is made up of a mixture of minerals, organic matter, water, and air.

Soils are important components of ecosystem sustainability because they supply air and water, nutrients, and mechanical support for plants. In turn, plants stabilize the soil with their vast root systems. By absorbing water during infiltration, soils provide water storage as well as delivering water slowly from upstream slopes to drainages and channels where it contributes to streamflow (Neary et al. 2005).

When a wildfire burns through an area with lots of fuel (combustible organic material such as tree leaves and needles, grasses, twigs, branches, and logs) on the ground, it sets the stage for that fire to burn hot and then smolder. This transfers quite a bit of heat downward into and through the soil. The greatest increase in temperature occurs at, or near, the soil surface. The more the soil heats, the more likely it is to experience destruction of its organic material and large changes in its mineral layer.

Ash and organic oils from burned plants coat the soil mineral particles, creating what is called a hydrophobic soil. This means that water is no longer absorbed into the soil, but rather runs off it along the surface. Instead of acting like a sponge, the soil acts like the basin of a kitchen sink.

As water runs off the soil and gathers momentum, it also gathers dirt, ash, rocks, sticks, and larger material. A trickle becomes a muddy flood called a debris flow. While debris flows can be triggered by events other than wildfire, they are more likely to occur following a high-severity wildfire which renders the soil hydrophobic.

“In the southwestern Rocky Mountains, moderate to severe forest fires can increase the likelihood of debris flow events by consuming rainfall intercepting canopy, generating ash, and forming water-repellant soils resulting in decreased infiltration and increased runoff and erosion. Debris flows, a destructive form of mass wasting, create significant hazards for people, and cause severe damage to watersheds and water resources”

Impacts on Water-Supply Reservoirs

Debris flows can overfill riverbeds and drainages, tear out trees and move boulders, and can destroy homes, businesses, and entire towns in a slurry of sludge. They can also fill water-supply reservoirs with a heavy load of sediment, taking the reservoir off-line in the short-term and forcing municipal water suppliers to rely on a secondary water source for residents, shortening the reservoir lifetime, increasing maintenance costs, and potentially rendering reservoirs unusable for storage or potability. Several municipalities across the state of New Mexico have had to spent millions of dollars to dredge their reservoirs following sedimentation events. Visit the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition’s Source Water webpage to learn more.

Post-fire Water Quality

Water quality can be compromised by wildfires both during active burning and for months and years afterward. As discussed above, burned watersheds are prone to increased flooding and erosion, which can negatively affect water-supply reservoirs, water quality, and drinking-water treatment processes.

Sediment which is transported off of the land and into waterways during post-fire flooding and erosion often contains a lot of nutrients, dissolved organic carbon, major ions, and metals. These elements can make treating water to make it safe for drinking more difficult; they can also result in algae outbreaks, which reduce the amount of dissolved oxygen available to fish and other aquatic species. The use of fire retardants during suppression of a wildfire could also have significant effects on downstream nutrients.

Runoff from burned areas contains ash, which may have significant effects on the chemistry of receiving waters such as lakes, wetlands, reservoirs, rivers and. Runoff from burned areas also produces higher nitrate, organic carbon, and sediment levels, warmer temperatures, and more unpredictable streamflows. The increased turbidity (cloudiness caused by suspended material) of this runoff leads to changes in source-water chemistry that can alter drinking-water treatment. Heightened iron and manganese concentrations may increase chemical treatment requirements and produce larger volumes of sludge, both of which raise water-treatment operating costs.